Gold Mining in Virginia

Potential mining threatens the Commonwealth's water.

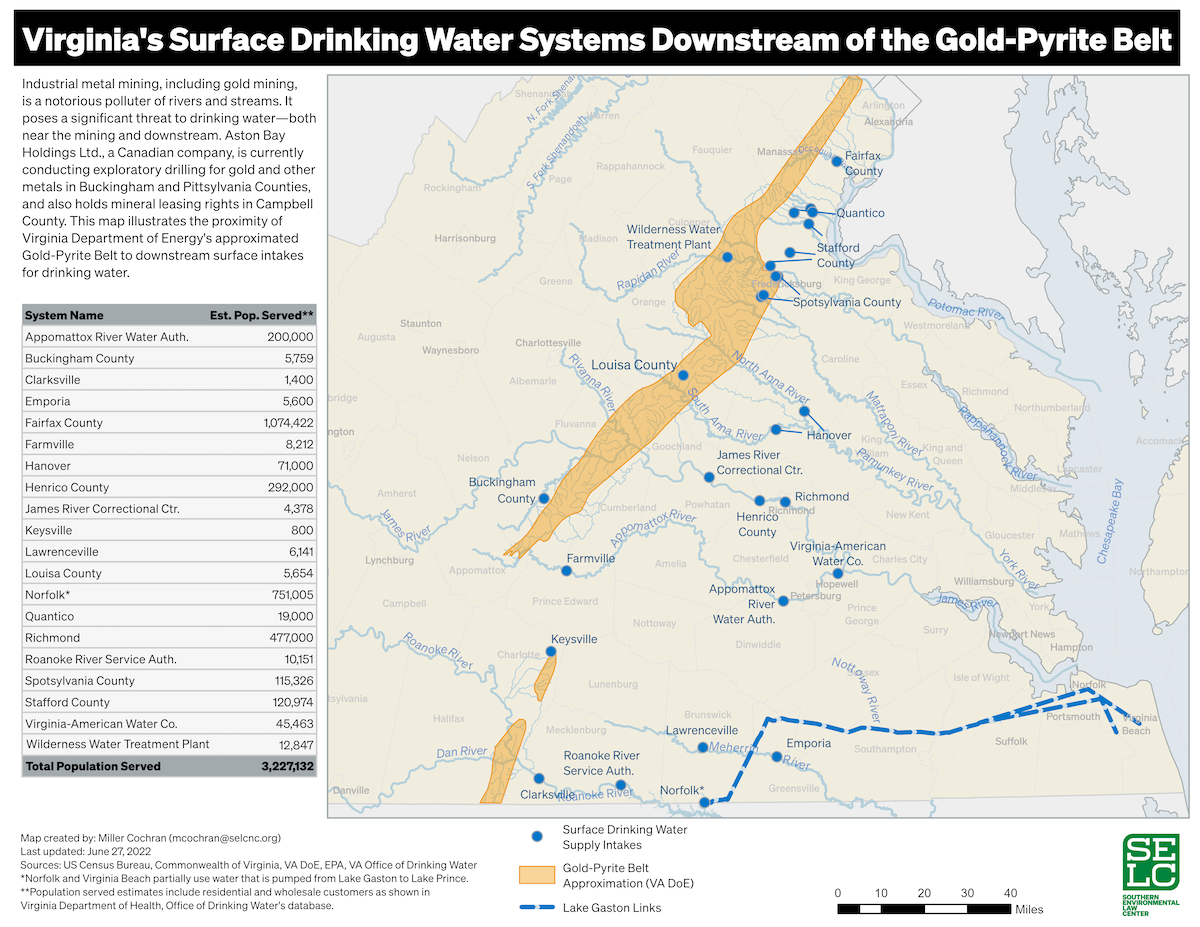

Gold mining has a long history in Virginia, with much of the mining taking place before the discovery of gold in the American West. Virginia’s Gold-Pyrite Belt stretches in a long, narrow band from Halifax County in the southern part of the state to Fairfax County in the north, though there are abandoned gold mines throughout the Commonwealth.

The impacts of these legacy mines are still felt today. Toxic chemicals used in historic mining operations – such as mercury – and ongoing acid mine drainage from these sites continue to pollute our waters.

Now after 75 years of dormancy, the future of gold mining in Virginia is uncertain. Canadian mineral exploration company Aston Bay Holdings Ltd. has started exploratory gold drilling in Buckingham County. In 2019, it expanded its search for metals into additional localities in the Commonwealth, including Pittsylvania and Campbell Counties. Gold mining activities bring significant risks, and communities are rightly concerned.

Because Virginia has no experience with modern, industrial-scale gold mining, the General Assembly voted in 2021 to fund a state agency committee to evaluate the impacts of gold mining activities on public health, safety, and welfare. In short, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s report, which was incorporated into the committee’s final document, found:

“Virginia’s current regulatory framework is not adequate to address the potential impacts of commercial gold mining…which poses a fiscal and environmental risk to the Commonwealth.”

The Commonwealth must develop comprehensive protections for communities, drinking water, and the environment from the impacts of modern, industrial-scale gold mining. Without that, it is up to individual localities to protect themselves.

What are the risks?

The environmental and public health impacts from gold mines in the U.S. are well-known and widely documented. Damage typically occurs through hazardous leaks, spills, and accidents; acid mine drainage; and airborne pollutants.

Cyanide is used to extract over 90% of gold mined in the U.S.

Acid mine drainage threatens human health.

Wastewater spills contaminate waterways.

Air pollution can also lead to ongoing and chronic health issues for those living near mines. Gold mining generates dust and airborne pollutants that are carried by wind into surrounding communities. Soil contaminated with toxic metals poses a substantial risk to small children, who are more likely to accidentally ingest these metals and are physiologically more vulnerable to metal poisoning.

A toxic legacy

Hundreds of abandoned gold mines can be found in Virginia’s Gold-Pyrite Belt and beyond – meaning unknown toxic legacies exist from Halifax to Fairfax. These mines existed prior to Virginia’s modern environmental laws and regulations, and most have not been properly assessed or remediated. Unfortunately, contamination from these abandoned mines continues to affect communities today.

One of the largest mines from this era, the Vaucluse mine in Orange, Virginia, illustrates the long-lasting damage gold mines can have on communities and ecosystems. The abandoned mine site has large open pits and small caved pits – physical remnants of its old mining operation. In 1988 the agency overseeing mining in Virginia (now called Virginia Energy) noted severe environmental harm at the site, including mercury contamination in stream sediments and “extremely acidic” mine drainage. The agency’s report recommended investigation into whether the site should become federally designated for priority cleanup as a Superfund site. The segment of the Rapidan River adjacent to the property has been listed as “impaired” under the Clean Water Act since 2010 due to mercury found in fish tissue.

Since reclamation of the site has not occurred, mercury contamination and acid mine drainage likely remain. Orange County is now considering a proposal to rezone the property for a mixed-use development that would allow up to 5,000 residential units on and around the old Vaucluse mine site. Organizations working in the County and community members are raising concerns about the site’s legacy contamination and the public health and safety risks, and they are pushing for cleanup of the property.

What are the risks?

In addition to the toxic legacies at abandoned gold mines around the Commonwealth, modern gold mines pose a host of new risks at each stage of operation – exploration, development, mining, processing, closure, and reclamation. These risks include impacts to public health, air and water quality, destruction of the landscape and wildlife habitat, and social and economic changes in nearby communities. A National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine’s report identified the following as significant potential impacts of gold mining in Virginia.

Acid Mine Drainage

Acid mine drainage is a serious problem that occurs when the mining process exposes previously buried rock (containing pyrite and other sulfide minerals) to air and water. Acidic runoff from the open-pit and underground mines mobilizes metals into the surrounding soil and water that are dangerous to human health and the environment. Toxic metals of particular concern in Virginia include antimony, arsenic, cadmium, lead, mercury, and thallium. These metals have myriad impacts on wildlife. Humans can be impacted by drinking or using contaminated water. In addition, soil contaminated with toxic metals poses a substantial risk to small children, who are more likely to accidentally ingest these metals and are physiologically more vulnerable to metal poisoning.

Cyanide Use

Cyanide is used to extract over 90% of gold mined in the U.S. It is extremely toxic to humans, animals, and some plants. Although cyanide is supposed to be managed carefully to avoid harm to human health and the environment, there are many examples of accidental releases from gold mining operations that have harmed humans, as well as resulted in mass mortality events for fish and other wildlife.

Nitrogen from Blasting

The blasting process can release excessive nitrogen into surface waters, posing risks to human health – especially for infants – and the environment. Nitrogen loading can cause algal blooms which can kill invertebrates and fish. Nitrogen from blasting in Virginia’s Gold-Pyrite Belt could have negative impacts as far away as the Chesapeake Bay.

Tailings Storage Failures

Tailings storage facilities can fail, quickly releasing large amounts of toxic metals into the environment. These catastrophic events can lead to human deaths or serious injury and severe property damage.

Loss of Groundwater

To mine a pit or underground mine, the water must be pumped out. “Dewatering” the mine can disrupt the flow of groundwater and result in nearby wells running dry. Rivers, lakes, and springs connected to groundwater can also be depleted by mining-related groundwater withdrawals.

Mining Activities Harm Air Quality

Exhaust from mining vehicles, as well as air emissions from mining activities, can harm local air quality and public health. Additionally, mercury from legacy mines can end up in the gold processing stream, get emitted into the air, travel far downwind, and be redeposited in soil and water, resulting in faraway impacts.

A cautionary tale

South Carolina’s experience with modern gold mining serves as a cautionary tale about the impacts of this industry. The Brewer gold mine, just outside Jefferson, South Carolina, has a long history of releasing illegal and harmful amounts of cyanide, mercury, and thallium into the surrounding environment.

In 1990, a dam broke at the mine after large rainstorms. This failure caused more than 10 million gallons of cyanide solution to escape into Little Fork Creek and Lynches River, resulting in a fish kill that persisted for nearly 50 miles downstream. Later, acid mine drainage from several seeps at the mine site threatened the same creek. When the gold mining company abandoned the site in 1999, the federal government was forced to step in and declared the mine a Superfund site. Expensive work to monitor and clean up the mine site will be necessary for decades – if not centuries – into the future, saddling generations of Americans, and especially South Carolinians, with the burden left behind by a gold mining company.

Virginia at a crossroads

As concern over modern, industrial-scale gold mining grows, Virginia is at a crossroads. The state agency committee’s findings on gold mining are clear and the report states that Virginia’s existing regulatory framework is “not appropriate” for gold mining. The accompanying National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine’s report found the same, calling the regulatory framework inadequate to address the potential impacts of commercial gold mining.

You can read the combined report here.

To date, there has been no action at the state level to address these shortfalls, leaving communities around the Commonwealth vulnerable to the risks associated with modern gold mining activities.

It’s clear that the status quo is completely inadequate to protect communities and the environment from the impacts of modern gold mining. The risks associated with the industry are just too great for our communities right now.

Carroll Courtenay, Staff Attorney in SELC’s Charlottesville office

With inadequate protections at the state level, communities are advocating for action at the local level. For example, residents in Buckingham County are concerned about the impacts of exploratory drilling and possible future gold mining activities in their community. Local land use tools, such as comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances, can be used to allow, restrict, or prohibit gold mining depending on the goals and priorities of individual communities.

Learn more about efforts to protect Virginians from industrial metals mining: