Protecting Atlantic waters from seismic blasting’s “storm of noise”

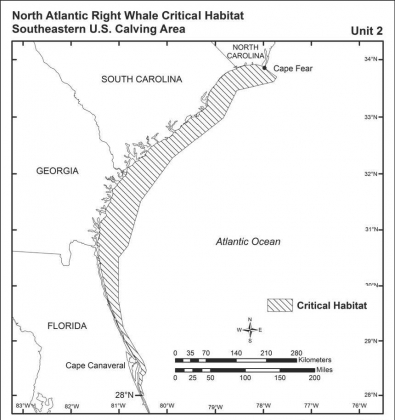

Marine scientist Christopher Clark has been listening to the world’s oceans for more than forty years. Off the coast of Virginia, using simple underwater microphones, the Cornell University bioacoustics expert has heard the rumblings of blue whales across the Atlantic and the calls of North Atlantic right whales swimming through their coastal calving grounds between Cape Canaveral, Florida and Cape Fear, North Carolina.

Increasingly, however, the sounds of marine life are being drowned out by the industrialization of the sea. Heavy shipping traffic floods the Atlantic Ocean with intrusive, ambient sound, and as companies line up for permits to search for oil reserves off the Southeast coast, the powerful air guns used in seismic surveys could soon add even more harmful noise to the underwater din. In fact, says Clark, air gun blasts are “orders of magnitude louder than the loudest ships,” producing a “storm of noise” that would severely disrupt the ocean environment off our shores, threatening marine mammals, critical fisheries, and the habitats of endangered species.

Last January, it appeared the Southeast Atlantic would be spared from the worst sonic harm. Community opposition to offshore oil and gas exploration had convinced the Obama administration to protect the Southeast’s coastal waters from drilling in 2016, and the decision to deny all pending permit applications for seismic testing in the Atlantic followed in early 2017. After all, there is no reason to blast if you don’t plan to drill. But the Trump administration has overturned that decision and pledged to expedite offshore oil and gas exploration, adding yet more danger to the lives of whales and other marine mammals already threatened by climate change, shipping traffic, and the dragnet of industrial fishing gear.

Seismic surveys are harmful, and even deadly, because the “brain-rattling” blasts of air guns profoundly disturb the acoustic environment of the ocean, a world in which many species depend on sound to survive. On a typical survey, a ship towing an array of powerful air guns plows a vast tract of the ocean, firing cannon blasts of compressed air to the seabed every 10 to 12 seconds, 24 hours a day, for weeks or months at a time. The pattern of sound waves reflected back to the ship gives oil and gas prospectors a map of the underwater crust of the Earth, revealing the possible location of fossil fuel reserves.

While North Atlantic right whales are found all along the Atlantic coast, NOAA has identified an area spanning from southern North Carolina into Florida as critical habitat for the endangered whale.

Southeast coast crucial to right whales

Studies by the Department of the Interior estimate that the seismic proposals currently under review would cause more than 13 million harmful interactions with marine mammals in the Atlantic, killing or injuring 138,000 whales and dolphins. Among the whales likely to be killed or injured is the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, of which fewer than 450 remain.

Clark, the bioacoustics expert, has repeatedly highlighted the harmful impacts of seismic blasting. In 2015, he was the lead author of a letter to President Obama, co-signed by 75 marine scientists, “united in [their] concern over the introduction of seismic oil and gas exploration along the U.S. mid-Atlantic and south Atlantic coasts.” Noting that explosive airgun blasts profoundly disturb ocean life, the scientists warned that seismic surveys in Atlantic waters would have “significant, long-lasting, and widespread impacts” on the survival of entire populations of marine species, from tiny plankton to giant humpback whales.

In the acoustic environment of the sea, air gun blasts reverberate across the ocean for thousands of miles. From his listening station sixty miles off the coast of Virginia, Chris Clark can hear seismic blasting from ships just north of Brazil and off the coasts of West Africa and Nova Scotia. In the waters nearby, the noise is so extreme that whales abandon food, family, and habitat to get away from the sonic assault.

Scientists fear that seismic blasting in the Southeast’s coastal waters would have a similar effect on North Atlantic right whales. Driven to near-extinction by 1970 due to a long history of whaling—they get their name for being the “right” whale to kill for a plentiful harvest of oil—they are the most endangered large whales in the ocean today. Their population has hovered between 350 and 500 for decades, but the death of sixteen right whales since mid-April—the most recent discovered just days ago—is unprecedented. Marine scientists place the blame on ship strikes and entanglements in industrial fishing gear, but also point to the rapid warming of the ocean, which is likely disturbing the right whale’s feeding and breeding grounds.

When their senses aren’t being assaulted, right whales communicate freely and “see the ocean through sound,” which orients them to everything they need to survive, and thrive: a big patch of plankton, the call of a potential mate, the way to winter calving grounds, and for newborn whales, the whereabouts of their mothers.

Just now, expecting female North Atlantic right whales are about to swim from their summer feeding grounds, off the coast of Maine and Nova Scotia, to their calving grounds off the coast of the Southeast United States. Because of their role in the future of the population, the success of these animals in making the migration, and returning with their newborn calves, is especially important. Last year’s calving season, which brought only 5 whales into the world, was a scary signal of decline.

We are in an emergency situation with the North Atlantic right whale, and the idea that we’re going to risk the future of one of the South’s iconic species, while simultaneously putting our coast at risk of oil spills and industrialization is ludicrous,” said Senior Attorney Sierra Weaver. “The need to protect the right whale is yet another reason to protect our coast.