Earth Month dialogues: Author chronicles neighbors winning against polluting hog farms

Writing about something as unappealing as industrial hog pollution wasn’t exactly what author and lawyer Corban Addison had in mind for his next book, but a phone call from a trusted friend changed everything.

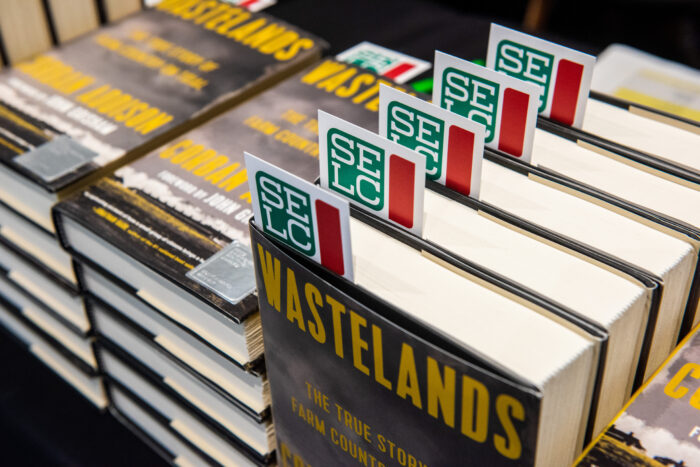

Wastelands: The True Story of Farm Country on Trial is Addison’s first nonfiction work. It showcases the coastal plain of eastern North Carolina as home to a close-knit, rural community that, for more than a generation, has pushed back against the polluting practices of industrial hog farms in their backyards.

SELC recently honored the international bestselling author with the 2023 Reed Environmental Writing Award for his thrilling chronicling of the years of frustration and futility faced by this community and their team of intrepid and dedicated lawyers who filed suit against one of the world’s most powerful companies.

Read our recent conversation with Addison to learn more about his experience of writing the book The New York Times is calling, “a damning portrait of how we feed ourselves.”

How did the industrial hog industry get on your radar?

I’ve eaten bacon for a long time and never thought about where it came from. It wasn’t until I got a serendipitous phone call in January 2019 when a buddy of mine told me about it. He’s from Salisbury, North Carolina, a small town where the lead trial counsel lives in the hog case that I documented for Wastelands, and they were family friends. He pitched me the idea of writing about it. I was hesitant at first, but I heard him out like I always do.

It must have been an intriguing conversation — how did it go?

What he told me was interesting. He had started thinking about the community down east, most of whom are Black people of modest means, and realized this might be a hidden civil rights topic, which immediately was of interest to me. It brought to mind A Civil Action by Jonathan Harr, a page-turning, true legal thriller that also has a civil rights element and inspired me to go to law school. I thought: If there’s a way to tell this story like that, I might be interested.

The most disgusting element of the story is the way that power and money are completely abused in this country and corporations are only held accountable, it seems, in the courthouse.

I agreed to meet with the lead attorney, Mona Lisa Wallace. When we met, she honestly wasn’t sure whether she wanted to open her life to me and have this story told, but she knew the clients deserved it — so she invited me to come to the fifth federal trial in Raleigh.

What did you find most impactful in your research for Wastelands?

I wanted to immerse myself in the story, to live it before I told it, and that required me to spend a lot of time down east with the people on the ground and up in the air. The up in the air part was an unforgettable experience. You cannot unsee what you see — just miles and miles and miles of hog barns, every single one of them with a thousand market hogs inside. Some farms have 15 or 18 barns. You’re talking about an enormous number of pigs, producing the waste of small cities that is then held in these giant, open-air cesspools.

From a height of a thousand feet, you can almost, in some places, see the equivalent of half a million hogs. They’re all living indoors, they never see the sunlight, and they’re constantly defecating and urinating, which gets sloshed out into this pit that then gets sprayed out into fields next to people’s homes. When you see these giant pink lagoons full of floating solid waste, which is black, suddenly you’re like: Wait a minute, is this the way we’re feeding ourselves in this country? Have we lost our marbles?

What else do you want people to know about the hog industry?

It is an absolute juggernaut of power in politics and economics. I write a lot about power dynamics in my books, and it offends me to the core that America is structured in such a way that these gigantic, multi-billion-dollar corporations can basically pull the levers of government and get free passes on abusing people and polluting the environment. It is sickening to me that our government, which is supposed to be of the people, by the people, for the people, is for corporations who can pad the pockets of the lobbyists and fund the campaigns of local officials to get their way in Congress and in state houses.

The most disgusting element of the story to me is the way that power and money are completely abused in this country and corporations are only held accountable, it seems, in the courthouse.

Your first four books are fiction, but still centered around human rights issues. What drives you to write about human rights, including environmental justice?

I went to law school at the University of Virginia here in Charlottesville because I have a passion for justice. It really bothers me when I see the world upside down — the powerful taking advantage of the weak and the corruption in systems, so I’ve always believed in the noble power of the law to even the scales and to give even the most disenfranchised people among us a day in court and an opportunity to be heard.

I practiced law in the courts for years, but I was always a natural storyteller. I’ve always conceived of my writing as basically practicing in the court of public opinion. I’m an advocate. I’m telling a story with the purpose of moving a heart in the same way that a trial lawyer standing in front of a jury is telling a story to move 12 hearts. It’s very similar.

Any advice for writing about complex legal work in an approachable and engaging way?

I’ve learned over the years to distill, distill, distill. Metaphors are a good way to translate complex topics into everyday parlance. As a novelist, a book doesn’t work unless it keeps the pages turning. You have to have an engaging plot and dimensional characters that you love or hate. At the very same time, you’re telling a true story and it comes down to a sense for storytelling, which I think is pretty innate. You can sort of learn how to do it, but in many ways, you have to have an instinct for it.

What gives you hope?

As a lawyer, I’m grateful for the courthouse. I think it would be really hard to be hopeful in an America that didn’t have an independent judiciary, or didn’t have groups like SELC and lawyers like Mona Lisa Wallace.

What writer has influenced you most?

I read all of John Grisham’s books when I was younger. I didn’t know any lawyers, but I read courthouse dramas and wanted to be a lawyer like that. Since then, John Grisham has done a whole lot for me and wrote the foreword of Wastelands.

Do you find any area of SELC’s work particularly interesting?

Here’s the truth: When I was in law school, I wanted to work at a place like SELC. I love SELC and its focus on impact litigation, bringing cases, and challenging laws and misbehavior out there in the world.