North Carolina’s hog problem

By Samantha Baars, Photos by Cornell Watson

In eastern North Carolina, where pigs outnumber people 30-1, it’s not uncommon for folks living near the region’s many hog operations to keep candles burning to tolerate the odor.

“I’m about three miles away from the Smithfield processing plant and some days I can smell the stench all the way at my house,” says Sampson County resident Sherri White-Williamson. “And there are people who live within 100 yards.”

Layered on top of these unpleasant smells is air and water pollution from various components of the commercial hog industry that proliferate across this rural part of North Carolina, which is known for its agricultural heritage and rich farmland.

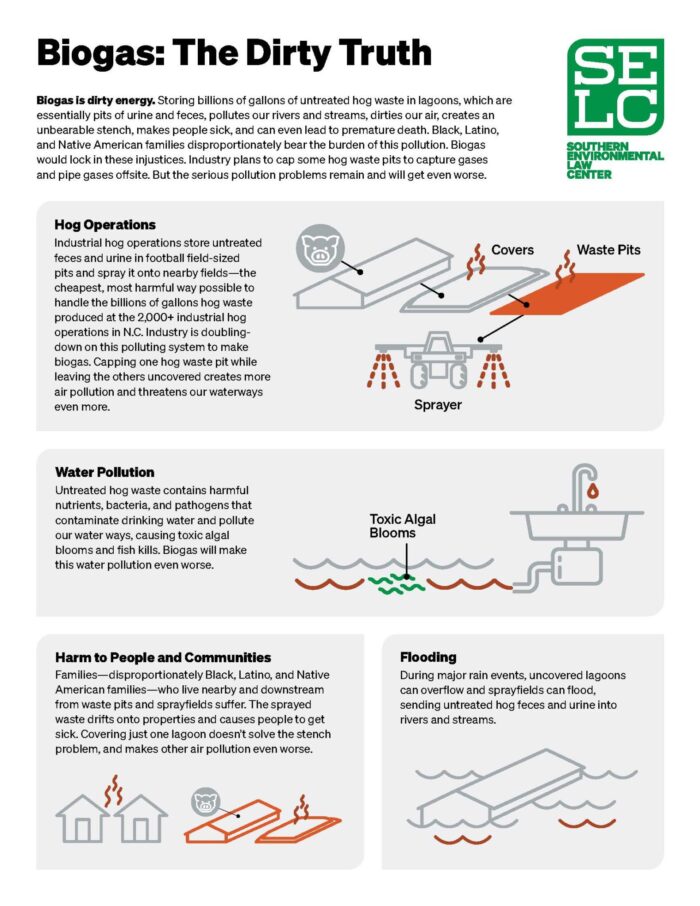

The landscape is too often interrupted by warehouse-sized holding pens, facilities that turn hog waste into energy that the industry calls biogas and claims is good for the environment, and industrial hog operations that store and spray billions of gallons of hog feces and urine onto nearby fields.

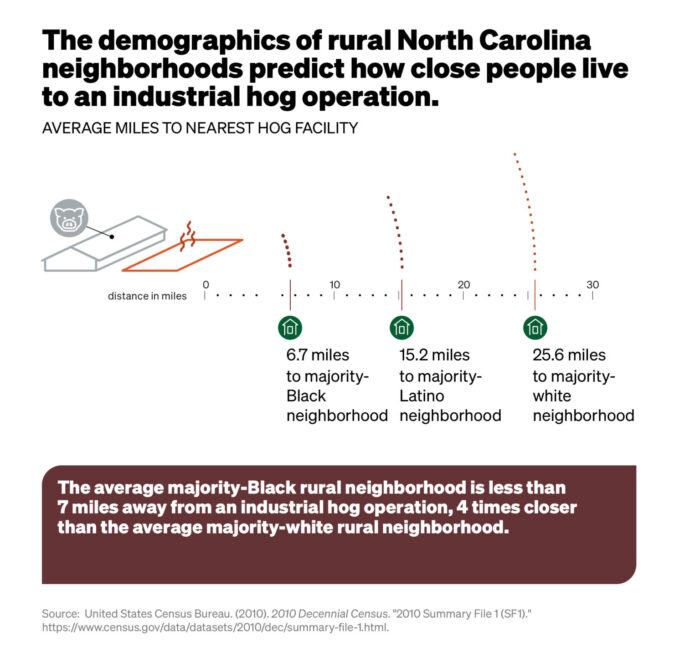

SELC is representing Sampson and Duplin County residents pushing for protections from the hog industry that primarily dumps pollution on Black and Brown, Latino, and Indigenous communities, and areas where household income is below the state average.

Holding polluters accountable

In 2022, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency made a landmark civil rights decision in response to a complaint SELC filed on behalf of the Duplin County Branch of the North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and the North Carolina Poor People’s Campaign.

For the first time, EPA agreed to investigate the discriminatory impact of pollution and adverse health risks, including premature death, that industrial hog operations making so-called biogas impose on primarily Black and Latino communities in eastern North Carolina.

It is an important look by a federal agency examining the local intersection of the climate crisis and environmental injustice.

“The state has a responsibility under the law to protect people from pollution,” says Senior Attorney Blakely Hildebrand. “Current plans for biogas are poised to double down on public health and environmental harms that the industrial animal industry has caused for decades, particularly in communities of color and low wealth communities.”

Hildebrand leads SELC’s work to stop and mitigate pollution from industrial hog operations. A lifelong North Carolinian, she has been strategizing on how to best support grassroots community groups since joining the organization in 2014.

Most recently, in the summer of 2022, on behalf of the Environmental Justice Community Action Network and Cape Fear River Watch, SELC challenged a one-size-fits all permit issued by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality that would allow hog operations to use giant pits of untreated hog feces and urine to produce methane gas, or biogas, while spraying the harmful waste on surrounding fields with minimal oversight.

This outdated practice can increase water and air pollution and continues a long history of harm to the families — disproportionately Black and Brown, Latino, and Indigenous people — living nearby.

The reality is that the climate crisis serves as a multiplier on deep seated inequity.

William Barber III, Director, Climate & Environmental Justice at Climate Reality Project

The general permit also fails to comply with a state law requiring cleaner technology and does not include common sense protections against pollution for nearby families, waterways, or air quality.

Cleaner technologies for managing billions of gallons of hog waste were developed in North Carolina and address many of these concerns, but have not been widely adopted by the hog industry. The groups are asking the court to require DEQ to comply with a law requiring cleaner technology to manage hog waste.

“There are few environmental justice issues in our region that are as significant and as well studied,” says Hildebrand.

And SELC is uniquely positioned to stop this pollution. The organization has deep roots on the issue and in North Carolina, with initial legal work around hog operations beginning in the 1990s.

Adds Hildebrand, “Multiple cases are ongoing, and we will continue to bring our resources to bear in a way that centers and respects the history of this issue and the voices of those most affected.”

Progress through partnership

Sherri White-Williamson was part of the group of Vermont Law School alumni who started the Environmental Justice Community Action Network in 2020 to inform, educate, and empower communities to confront environmental injustice by advocating for change.

EJCAN started their work in Sampson County, the second highest hog-producing county in the country.

A Sampson county native, White-Williamson has made a long career of fighting for equity, including at the federal level in her former role at EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice. She worked in D.C. for about 20 years before returning to her hometown in Clinton, and upon her arrival, she says she was appalled.

“When I first moved back home, I was so taken aback by everything I saw that I became a pescatarian,” she says. It’s only been about a year since she found a local farmer she trusts enough to purchase their pork.

While White-Williamson says her work at EPA afforded her the “opportunity to see the breadth and depth of environmental injustices across the country,” it also illuminated that most people don’t think of the rural South when considering environmental inequities. “They think of smokestacks in the city.”

So White-Williamson has made it her personal mission to educate on rural environmental justice issues, and stopping pollution from hog operations is a priority for EJCAN.

EJCAN has mobilized its members to speak at public hearings, at the legislature, and locally about pollution from hog operations and other facilities.

White-Williamson is monitoring projects that may have an impact on her community and demanding more information from local elected leaders and business leaders, including a biogas processing facility in Turkey, a small community on the Duplin-Sampson county line. This facility is owned by Smithfield Foods and Dominion Energy’s joint venture, Align, and will be hooked up to almost two dozen hog operations to process methane and other harmful gases.

Just down the street from this Align facility is yet another waste processing plant.

The owner of the facility intends to pick up hog waste from nearby hog operations, truck it through town, and process several tons of it per day.

“There has not been a lot of information provided to the community, contrary to what the industry would say they’ve done to inform people,” says White-Williamson. “There is still a lack of understanding.”

Nicole Myers-Mobley also has questions, but few answers, about this new facility. She manages a property “a field away” and has spent a lot of time visiting with residents who want more information on their new neighbor.

The people closest to the problem are the people closest to the solution.

William Barber III, Director, Climate & EJ at Climate Reality Project

In the wake of a changing climate, the area — located in a low-lying coastal plain — is experiencing record flooding and other impacts from natural disasters. “Are they going to be set up for situations like that?” she asks. “What happens if waste seeps into Turkey Creek? What happens if there’s an overflow?”

The lack of public transparency combined with the continued encroachment of polluting facilities on communities reinforce ongoing patterns of environmental injustice throughout the South and beyond.

Sustaining the movement

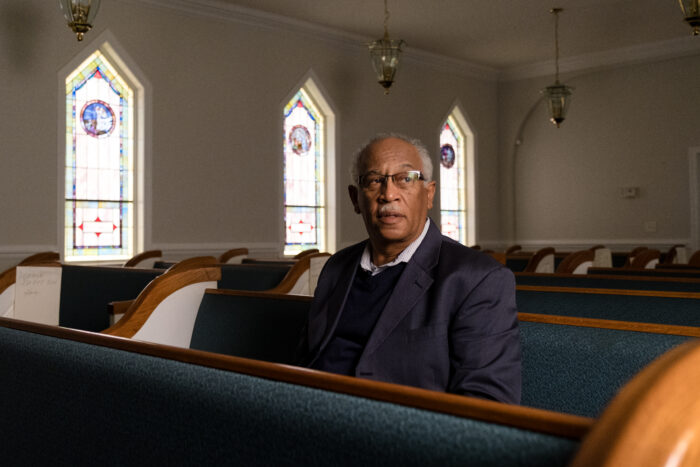

As the son of the distinguished climate and human rights advocate, Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, William Barber III developed a deep commitment to environmental and social justice at a young age.

He grew up in eastern North Carolina where he now serves as the Director of Climate and Environmental Justice at the Climate Reality Project and is on numerous boards focused on climate justice and equity issues, including the state DEQ’s Environmental Justice and Equity Advisory Board. He’s also the founder of the Rural Beacon Initiative, which helps businesses implement sustainable and equitable solutions.

“The reality is that the climate crisis serves as a multiplier on deep seated inequity,” says Barber.

Common themes revealed in Barber’s work to confront environmental injustice in communities of color and low-income communities include lack of transparency and information, industry encroachment, and the influx of ‘dirty’ businesses posing as environmentally friendly.

“The biogas and wood pellet facilities are especially sinister because on their face they look like technologies we need, but the reality is they are solutions that do much more harm,” he says.

He adds, “It’s incredibly disconcerting when we think of the urgency of the climate crisis, but also personally disturbing as someone who grew up in these communities in rural America and understands the continued encroachment communities are facing. We don’t have frank conversations about solutions that are good for the planet and good for the people.”

When prompted, he shares that environmental justice isn’t necessarily something that can be achieved. Barber expresses the importance of sustaining the movement for generations.

What is environmental justice?

Learn more about how we’re partnering for an equitable future.

“I think environmental justice truly is not a destination that we’ll reach with finality, but a framework through which we have to continue to analyze every decision being made that is affecting communities and individuals,” he says. “We have to commit to it and recommit over and over again.”

SELC works to ensure a healthy environment for all across the region, and will continue to take a place-based approach in supporting partners in the push for protections from hog operation pollution and other environmental injustices playing out across the South.

Barber’s closing thought serves as a good reminder to everyone working toward justice: “The people closest to the problem are the people closest to the solution.”