Virginia completes initial PFAS sampling, but study is limited

Limited sampling of Virginia’s public drinking water has revealed the presence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), according to a new report by the Virginia Department of Health. The study tested samples from 45 waterworks for 25 different types of PFAS, and PFAS were found in 15 of 63 samples. The report also examined the current science on PFAS compounds, as well as available regulatory approaches and treatment options.

“It’s not surprising that we’re seeing PFAS in Virginia’s drinking water,” said Carroll Courtenay, a staff attorney in SELC’s Virginia Office. ”The use of PFAS is so widespread that if you sample for them, you will find them. That’s why it’s so important to make sure that the industries making and using PFAS keep them out of our waters in the first place.”

What are PFAS?

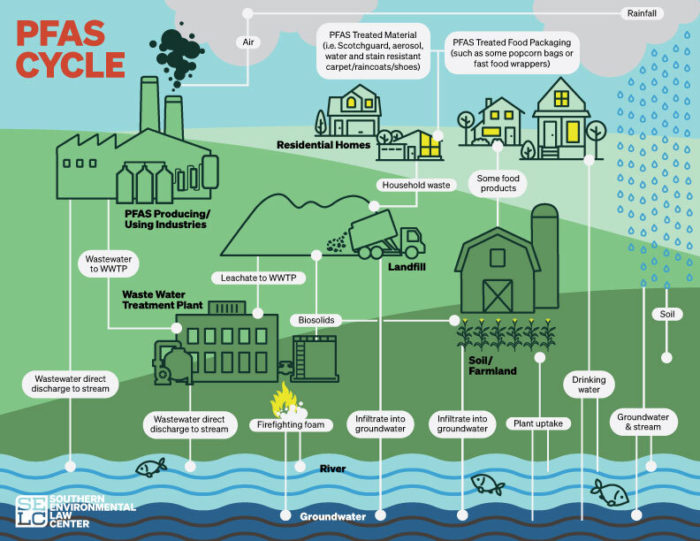

PFAS are a class of thousands of manufactured chemicals that have been used in products and manufacturing processes since the 1940s. Due to their extensive use, including in food packaging, waterproof and stain-resistant coatings, and personal care products, PFAS are now present in our water, soil, air, and food. Some of the most acute PFAS pollution issues come from facilities that manufacture PFAS or use PFAS in industrial processes—such as the Chemours plant in North Carolina—and airports and military bases where PFAS-containing firefighting foam has been sprayed.

“Since there are so many different PFAS compounds, it’s important that we look at these chemicals as a class,” Courtenay said. Regulating PFAS one by one not only delays protections for public health and the environment, but could also fail to address cumulative pollution issues caused by multiple types of PFAS. “We’re still learning a lot about these chemicals but we do know that they pose a significant threat to human health and the environment, especially because they bioaccumulate—or build up in humans and animals—over time.”

PFAS in Virginia: What we know so far

Prior to the VDH drinking water study, there were already several known instances of PFAS groundwater contamination in the Commonwealth. These sites include the DuPont Spruance plant outside of Richmond and several military and other government installations including NASA’s Wallops Island facility, Norfolk Naval Station, Oceana Naval Station, Joint Base Langley-Eustis, and Fentress Auxiliary Landing Field. Through the 2021 VDH drinking water study, PFAS were found at 15 of 63 sample locations. None of the concentrations were above the EPA’s lifetime health advisory level of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for two types of PFAS, PFOA and PFOS, and none exceeded any of the drinking water standards established by other states for these chemicals. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, however, is currently developing federal drinking water standards for PFOS and PFOA that are widely expected to be significantly lower than the current lifetime health advisory level.

The VDH study indicates that PFAS are present in drinking water from the Potomac River and Occoquan Reservoir, two major sources for waterworks in Northern Virginia. The highest PFAS levels were detected in Roanoke. Concentrations of over 50 ppt of HPFO-DA, more commonly known as GenX, were found in water from the Spring Hollow water treatment plant.

This drinking water study, however, was constrained in its scope. Legislation limited the study to sampling at 50 of the approximately 2,800 waterworks in Virginia. Funding limitations also generally meant that only one sample was taken at each location, which cannot account for variations based on manufacturing timelines or environmental factors. While the study provides a jumping-off point to inform future PFAS sampling efforts, more needs to be done to study PFAS contamination in Virginia and stop the pollution before it is released into our waters.

The burden should be on industries that use and discharge PFAS to clean up these chemicals before they reach our waterways, not on downstream communities. To help break the cycle, we need to work to stop PFAS pollution at its source.

Attorney Carroll Courtenay

For example, Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) recently announced an instance of PFAS surface water contamination above the EPA’s lifetime health advisory—contamination that was not identified through VDH’s drinking water study. Extremely high levels of PFAS were detected in the White Oak Swamp watershed of the Chickahominy River. Initial testing for 45 different PFAS compounds turned up concentrations of over 2,000 ppt at several locations downstream from the Richmond International Airport. DEQ has launched a multi-pronged study of PFAS in the area, including surface water testing and fish tissue sampling, and Henrico County is spearheading private well testing for nearby properties.

“The contamination in White Oak Swamp is a perfect example of why we cannot focus on PFAS contamination in drinking water alone,” said Courtenay. “The burden should be on industries that use and discharge PFAS to clean up these chemicals before they reach our waterways, not on downstream communities. To help break the cycle, we need to work to stop PFAS pollution at its source.”