Mobile Baykeeper, SELC sue Alabama Power to stop coal ash pollution in the delta

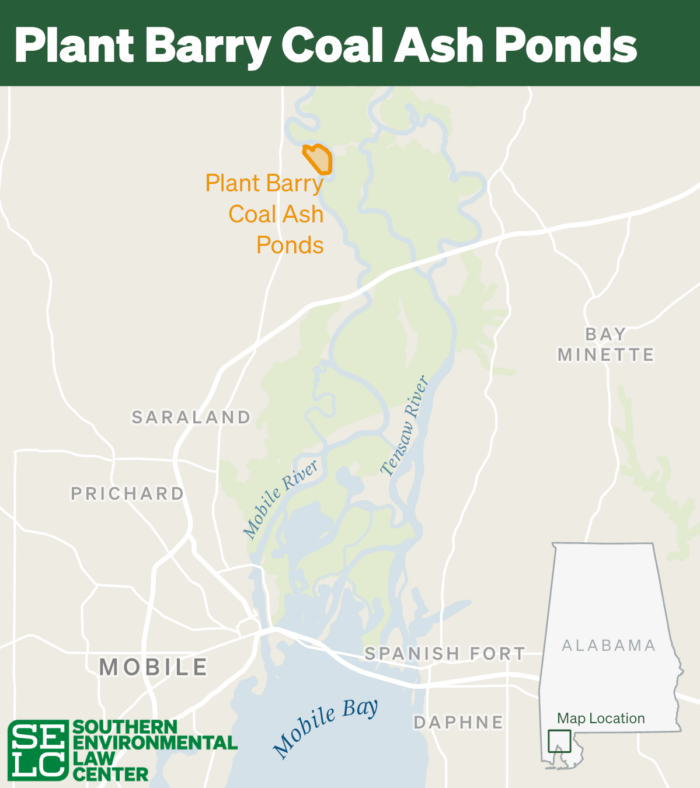

In September, the Southern Environmental Law Center and former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama Richard Moore filed a lawsuit on behalf of Mobile Baykeeper against Alabama Power. The suit challenges the company’s illegal plan to permanently leave more than 21 million tons of toxin-laden coal ash at Plant Barry in an unlined pit within the floodplain on the banks of the Mobile River.

“Plant Barry is the only coal ash lagoon of a major utility left in a low-lying coastal area of the Southeast that is not already cleaned up or on track to be recycled or removed to safe storage, away from waterways,” said Barry Brock, director of SELC’s Alabama office. “It is past time that Alabama Power faced up to the fact that leaving wet, polluting coal ash on the banks of the Mobile River is not a long-term solution — it’s a looming disaster.”

For decades, coal ash at Plant Barry has been contaminating groundwater with high levels of arsenic and other pollutants. Now that the utility is required by federal law to close and clean up its coal ash, Alabama Power presented a plan to continue storing millions of tons of coal ash in a pit next to the Mobile River, ensuring continued pollution.

Our supporters make this work possible.

America’s Amazon

Alabama’s Mobile region is one of the rainiest areas by volume in the United States. When the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta floods, it sends water across the delta down the Mobile and Tensaw rivers and into Mobile Bay. In recent years, there have been two major coal ash disasters when riverfront coal ash storage sites failed in Kingston, Tennessee (2008) — resulting in a $3 billion cleanup effort — and on the Dan River in North Carolina and Virginia (2014), releasing millions of tons of toxic coal ash into adjoining rivers and putting downstream communities and businesses at risk.

Alabama Power is the only major utility in the Southeast that is not excavating any of its unlined waterfront coal ash lagoons, and Alabama is the only Southeastern state where not a single unlined waterfront coal ash lagoon is being excavated.

The second largest delta in the contiguous United States, the Mobile-Tensaw River is a vulnerable wetland with inextricable ties to the health of the rivers and streams within it. As a result, the threat of an imminent coal ash spill in the Mobile River jeopardizes large portions of this extraordinary ecosystem.

“The Mobile-Tensaw River Delta and Mobile Bay are of incalculable value to Coastal Alabama,” says Cade Kistler, Baykeeper at Mobile Baykeeper. “These waters are the bedrock of the economy, quality of life, and environment in the region. Alabama Power’s plan allows groundwater pollution to continue indefinitely and puts coastal Alabama at risk of a catastrophic spill like those that have happened in Tennessee and North Carolina.”

The delta’s value is also in the key role it plays in supporting Alabama’s globally significant biodiversity. Deemed “America’s Amazon” by writer Ben Raines, the Mobile-Tensaw Delta is not only home to the coal ash lagoon, but one of the world’s most biodiverse bodies of water. In fact, the state’s rivers are home to more species of fish, crayfish, salamanders, mussels, snails, and turtles per square mile than any other aquatic system in North America, by a long shot.

At the same time, Alabama has suffered more aquatic extinctions than any other state and the state ranks last in spending on environmental protection. The state’s rivers contain populations of aquatic snails and freshwater mussel species unlike anywhere on the planet. The risk of a catastrophic coal ash spill in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta threatens a unique array of wildlife throughout the state, in addition to the well-being of local business and communities.

Explore how changing coasts will impact Plant Barry on our interactive map.

Catching up on cleanup

Meanwhile, across the region, every major South Carolina utility, Duke Energy in North Carolina, and Dominion Energy in Virginia, are excavating each of their unlined waterfront coal ash impoundments. More than 270 million tons of coal ash are being removed from unlined pits and our groundwater, thanks in large part to SELC’s legal efforts.

Alabama Power is the only major utility in the Southeast not excavating any of its unlined waterfront coal ash lagoons, and Alabama is the only Southeastern state where not a single unlined waterfront coal ash lagoon is being excavated.

Next door, Georgia Power — which is owned by the same company as Alabama Power — is excavating approximately 65 million tons from unlined coal ash impoundments, including a plan announced in June to recycle 9 million tons of coal ash into concrete at Plant Bowen.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Coal Combustion Residuals Rule, which governs the closure of coal ash lagoons around the country, contains multiple performance standards that prohibit utilities from leaving their coal ash sitting in groundwater. Yet at Plant Barry, where the coal ash is saturated by groundwater, that is exactly what Alabama Power’s closure plan would do. The law requires that owners of coal ash impoundments who cannot meet the performance standards for leaving coal ash in place must remove the ash to dry, lined landfill storage, or recycle it.

Alabama Power’s coal ash plans bring into stark relief the impossible tension between supporting the state’s incredible biodiversity and allowing unfettered pollution. Until Alabama Power removes coal ash from this unparalleled landscape, Mobile residents and hundreds of species vital to the ecosystem will rely on luck to keep catastrophe at bay.