Fighting forever chemicals

By Stephanie Hunt, photos by Cornell Watson

Carrol Olinger never planned on being a rabble-rouser.

She and her family loved the quiet, rural life in Hope Mills, North Carolina — a small town an hour south of Fayetteville, named for the cotton mills nearby. For years, Olinger was a teaching assistant at Alderman Road Elementary School and led Girl Scout adventures, taking her troop fishing along the Cape Fear River. “I enjoyed scuba diving and snorkeling in it too. It’s still fun even if you can’t see anything,” she says of the202-mile waterway — the state’s largest river system, which like many tannin-stained rivers, is often murky, like diluted chocolate milk. “But I don’t anymore.”

Not since Olinger, her neighbors, and the 500,000 North Carolinians downstream whose drinking water comes from the river learned that natural tannins aren’t the only thing muddying the Cape Fear.

These days, Olinger has traded scuba for diving deep into the river basin’s long history of industrial pollution, including the 40-plus years that DuPont and, more recently its spin-off, Chemours, have been discharging toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly known as PFAS, into the Cape Fear and contaminating groundwater. Like a seasoned scout leader, she’s determined, feisty, and outspoken about how that contamination disproportionately impacts “people who look like me — Brown and Black people. Those who don’t have health insurance and can barely pronounce polyfluora-whatever or reverse osmosis, much less afford it,” Olinger says.

“I’m an accidental activist,” she laughs, though she knows that these so-called “forever chemicals” are deadly serious. Their common name speaks to the durable, resilient qualities that make them useful in innumerable products — waterproof, stain-resistant, nonstick products, electronics, medical devices, beauty products, explosives, dental floss, you name it — but also to the fact that they don’t break down in the environment and our bodies. PFAS have been linked to cancer, kidney and liver disease, immune dysfunction, endocrine disruption, infertility, asthma, and low birth weight, among other conditions. “Here I am on dialysis, with no family history of kidney disease,” Olinger says.

I’m an accidental activist.

Hope Mills, N.C. resident Carrol Olinger

When the Wilmington StarNews broke the story in June 2017 that the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority was contaminated by GenX, a PFAS compound discharged by Chemours, “It started making sense, why I was sick and the fish in my fish tank were dying,” says Olinger.

She is now an area organizer for Action NC, a statewide advocacy group addressing social and economic inequality. Realizing there was more to the story, “Dig deeper!” became Olinger’s rallying cry at local protests and public hearings.

Stopping pollution at its source

Like Olinger and most North Carolinians, SELC Program Director Geoff Gisler first learned of the Cape Fear’s contamination from that newspaper story. Then serving as SELC’s Water Program lead, Gisler didn’t just dig deeper, he excavated. “We worked with our partners at Cape Fear River Watch

to learn as much as we could, and to strategize how best to hold the polluters accountable,” Gisler says.

The Clean Water Act already provides the means to do so, he explains, but manufacturers like Chemours were taking advantage of lax enforcement and the public’s lack of awareness at the time. Chemours continued to profit as they released contaminated discharges; meanwhile taxpayers and ratepayers were footing the bill for testing and for upgraded filtration systems: $43 million for the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority alone, with an additional $5 million in annual maintenance costs. Brunswick County will spend more than $100 million upgrading its drinking water plant to filter out Chemours’ pollution. “Chemours was completely reckless and ignored what they knew to be the reality of these chemicals,” says Gisler.

DuPont and 3M, in fact, have known for decades that PFOA, an earlier type of PFAS, and later modifications, including GenX, are dangerous. DuPont’s own findings dating from 1965 suggest as much, and later studies from the 1970s to the present consistently point to concerning public health impacts.

At the end of the day, we all just want to go home and feel safe when we turn on the tap. We want that for everyone.

SELC Program Director Geoff Gisler

Despite increasing awareness that PFAS are a threat to communities, industry continues to try to avoid responsibility for pollution by claiming scientific uncertainty. “Based on the information we have, we know enough to act,” Gisler asserts, contradicting claims that more information is needed to establish safety levels. The Clean Water Act of 1972 was designed to eliminate all water pollution of every kind by 1985, explains Gisler, “and that is our goal, to stop water pollution at its source. Period.”

Dana Sargent, executive director of the nonprofit Cape Fear River Watch, agrees. “PFAS shouldn’t be in the drinking water of millions of Americans,” Sargent wrote in a 2020 op-ed, a year after her 47-year-old brother, a firefighter, died of a brain tumor after a career of exposure to cancer-causing PFAS chemicals used in firefighting.

As a former journalist and communications specialist turned clean water advocate, Sargent knows how to go after a source. Alongside Gisler, she was already “full force” into learning about PFAS, but with her brother’s diagnosis in 2017, “it became personal,” she says. Similarly, her colleague, Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette, had grown up along the Lower Cape Fear, and his father was battling kidney cancer. “There was no question that SELC would be our partner in this fight,” says Sargent. “I have massive trust in their knowledge and expertise. They totally have our backs.”

In May 2018, SELC filed a lawsuit on behalf of Cape Fear River Watch against Chemours and government officials for not acting fast enough to stop the toxic pollution. In 2019, SELC reached a settlement with those officials and Chemours that required a massive cleanup, with the company agreeing to cut water and air pollution by at least 99 percent.

Broadening impact

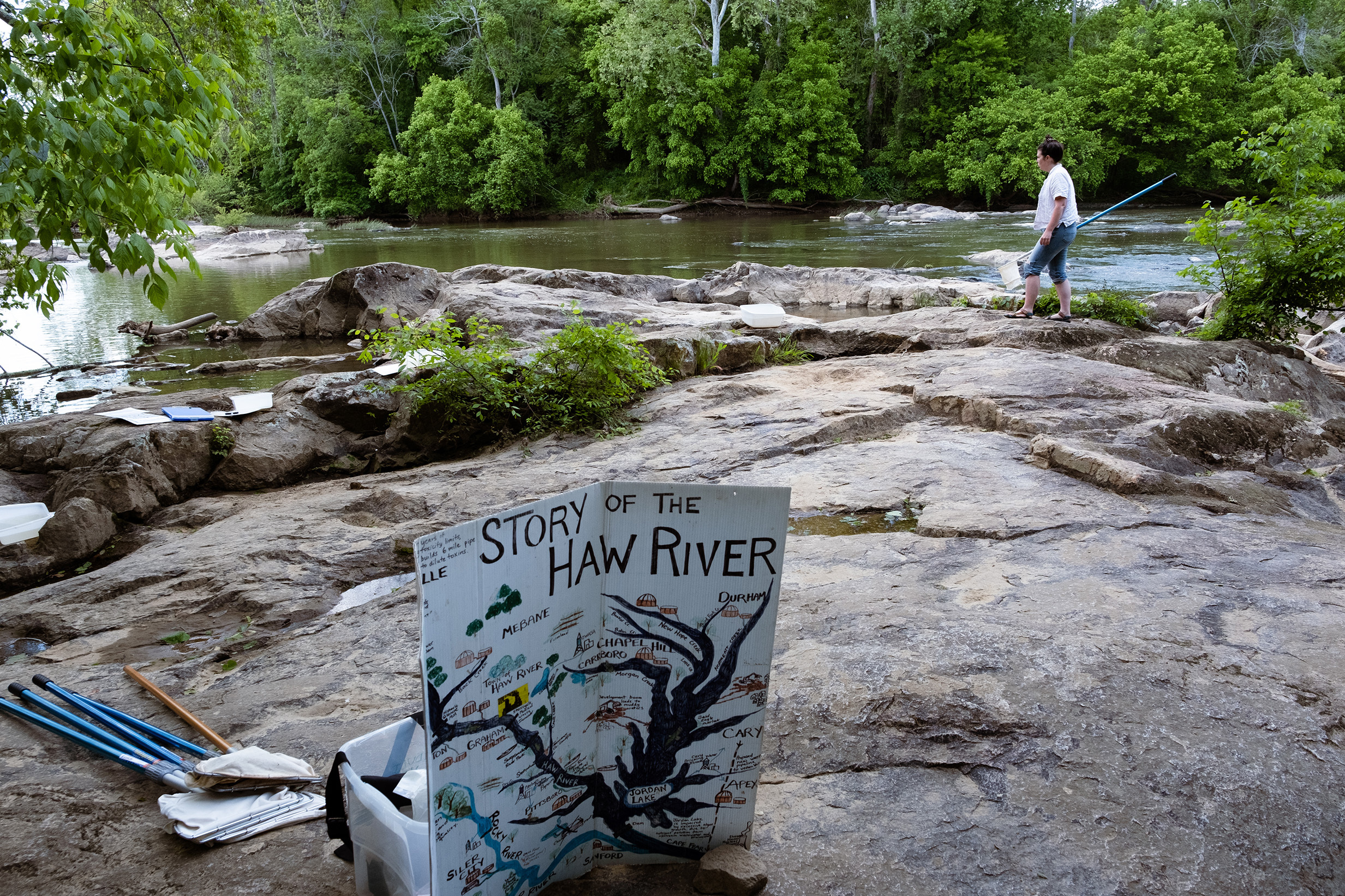

SELC’s wins in North Carolina, both in the Chemours case and in Burlington and Greensboro, where wastewater treatment plants were discharging contaminated water into the Haw River, which is part of the Cape Fear River system and water source for communities including Pittsboro and Chapel Hill, have already had positive effects, driving policy changes. SELC leveraged its expertise to “push the state to finalize the most effective permit in the country,” says Gisler, “and we continue to push for stronger oversight and enforcement by state agencies.

Today these efforts are reflected nationwide in the EPA’s new guidance to states, directing them to use existing powers under the Clean Water Act to stop PFAS pollution at its source and hold polluters accountable. And in March 2023, when EPA Administrator Michael Regan announced the first-ever proposed national drinking water standards for six PFAS chemicals, as well as a requirement for municipalities to test for 29 PFAStypes, he did so on the banks of the Cape Fear River — reinforcing the influential role SELC and local partners have played fighting these toxic forever chemicals.

The work, however, is far from over. As public awareness grows and testing for PFAS expands, combatting forever chemicals might feel like a forever fight. Even so, every victory is powerful. In Northwest Georgia, where PFAS-producing textile and carpet manufacturers are plentiful, SELC was able to trace PFAS contamination to Mount Vernon Mills, a textile plant on the Chattooga River in Trion, Georgia. Unlike Chemours, the Georgia polluter wasn’t putting pollution straight into the river; instead the mill was sending PFAS-polluted industrial wastewater to the City of Trion’s waste-

water treatment plant. Like nearly all municipal water treatment facilities, Trion’s was not equipped to remove these chemicals, which then contaminated the plant’s sewage sludge and eventually the surrounding watershed.

“Industrial polluters are required by law to control PFAS pollution instead of placing the burden on communities downstream,” says Chris Bowers, an Atlanta-based SELC senior attorney who used that argument to file a Georgia civil suit on behalf of Coosa River Basin Initiative. Under the resulting March 2023 court-enforceable agreement, Mount Vernon Mills must permanently halt PFAS use at their Trion facility this year. Prevention, notes Bowers, is the ideal method to control pollution.

Think big. Let’s stop forever chemicals at the source.

Nimble and vigilant

According to Gisler and Bowers, these successes all come back to having engaged citizens and to partnering with the grassroots organizations SELC represents. “Like SELC, our clients are nimble and uniquely suited to identify problems and help us quickly drive toward fixes,” Bowers adds. “We will continue to lead the way in our region, putting industry and the regulated community on notice that they have an obligation to handle these dangerous chemicals lawfully, that there’s no more waiting.”

The ultimate goal is to bring hope back to communities like Hope Mills. “We can make the legal

arguments, but it’s the personal stories of people like Carrol and Dana that move decision-makers. Sure, many might think a 99 percent PFAS reduction is great, but when you see the emotional toll of what that 1 percent means to a community who has suffered decades of exposure, that changes things,” says Gisler. For years, families like the Olingers enjoyed what they believed to be their “idyllic rural life, with their land and garden, their little patch of the world they feel safe in,” he adds. Discovering their water is unsafe robs them of that peace. “At the end of the day,” Gisler says, “we all just want to go home and feel safe when we turn on the tap. We want that for everyone.”