New EPA study of GenX toxicity highlights need to better regulate all ‘forever chemicals’

Updated November 4, 2021:

After EPA’s recent GenX toxicity assessment, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality sent two letters to Chemours that follow up on the terms of the 2019 consent order resulting from SELC’s litigation on behalf of Cape Fear River Watch to stop PFAS pollution.

A link to each letter can be found here and here.

SELC senior attorney Geoff Gisler comments, “The consent order was designed to take immediate action to address pollution we understood at the time and to require additional protections to be implemented when new information was discovered. Now, DEQ is following through on the consent order by starting the process to incorporate the new GenX toxicity assessment and demanding a more extensive investigation into off-site groundwater contamination.”

The original article appears below:

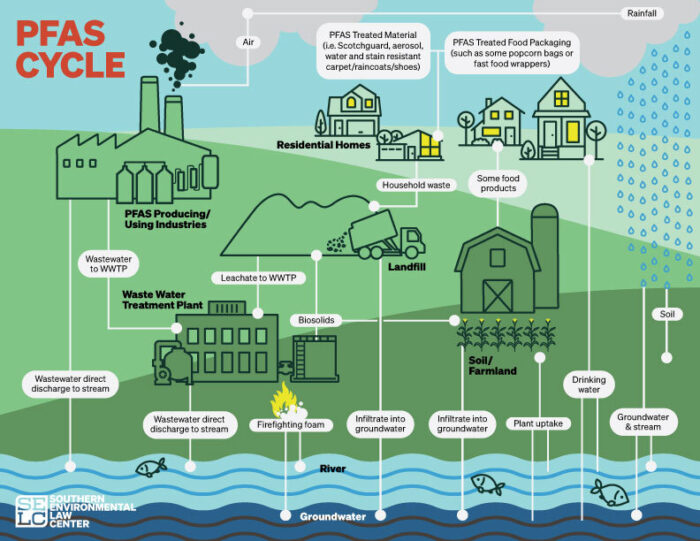

The Environmental Protection Agency’s release of its final human health toxicity assessment for the chemical GenX underscores the importance of regulating it and similar chemicals, known as PFAS, as a class of chemicals. The findings also reinforce the need to stop harmful pollution at its source, using laws already on the books.

We used this strategy, of legal action to require implementation of existing laws, with our partners at Cape Fear River Watch to reach an agreement that is stopping pollution at its source – a facility owned by Chemours along the Cape Fear River in North Carolina.

“This toxicity assessment is further confirmation that the more we learn about these chemicals, the more we learn that they must be treated as a class; no community should have to suffer from harmful PFAS as we wait for research to confirm their toxicity,” said Senior Attorney Geoff Gisler, leader of our Clean Water Program. “This more stringent GenX toxicity assessment shows why it’s so vital to our families and communities that DEQ, and state agencies nationwide, impose stringent limits on PFAS, using existing authority when issuing water permits to polluters.”

SELC’s litigation led to a consent order among Cape Fear River Watch, the state and Chemours to stop, at its source, at least 99 percent of PFAS pollution that contaminated the Cape Fear River. The more stringent standards for GenX likely will increase the number of people near the Chemours Fayetteville Works Facility and rely on drinking water wells who qualify for filtration paid for by Chemours under the consent order.

As pollution controls under the 2019 consent order are implemented, levels of GenX discharged from the facility, which produces chemicals used in non-stick products like Teflon, decreased significantly, but the legacy of decades of PFAS pollution still burdens communities downstream with treatment costs and health harms.

GenX has been at non-detectable levels in nearly all treated water discharges at the Fayetteville Works Facility since implementation of controls in the consent order. The controls are also effective in removing other PFAS, demonstrating the availability of technology to keep PFAS out of drinking water supplies.

GenX is part of a broad group of about 5,000 chemicals long known to be toxic. In the past, when one of these compounds drew concern, manufacturers changed the chemical makeup slightly, in part to avoid having to meet health and environmental standards. This sleight of hand is possible when EPA evaluates each chemical individually. Shifting to setting levels for the whole class of chemicals at once, as we’re urging, will avoid the current whack-a-mole approach to protecting people’s health and drinking water sources.

SELC and our client, Cape Fear River Watch, continue to enforce the terms of a resulting consent order with the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality and Chemours to stop the GenX and other PFAS pollution at its source and ensure the Cape Fear River is safe for downstream communities. The river is the drinking water source for Wilmington, N.C., and Pender and Brunswick Counties downstream. GenX and other PFAS have been found in their treated drinking water at high levels.