The biomass climate hoax

By Alexandra Marvar, photos by Julie Dermansky

It’s a sunny April day in Adel, Georgia, the seat of Cook County, about 150 miles south of Macon on I-75.

The last azalea blossoms are dropping to the ground, cedar waxwings are trilling, and neighbors’ porch visits cover the usual topics: the weather, who’s moving in or out of town, and the latest talk about what kind of pollution might come with the new business setting up down the road.

Community organizer Dr. Treva Gear is even-keeled about the possibility: This is just another hazard in the whac-a-mole game of industrial development she has been trying to win since moving back to her hometown.

An Army veteran and former educator, Gear now works with the forest-focused environmental justice group Dogwood Alliance, helping Adel survive an onslaught of polluting industries. That has included everything from a propane refurbishing plant’s noxious chemicals to a crypto-mining operation’s helicopter-like noise, day and night. Increasingly, Dogwood Alliance, SELC, and other environmental organizations have been zeroing in on a different threat to Southern neighborhoods, forests, and global climate progress: the wood pellet industry.

Gear and her neighbors formed the grassroots organization Concerned Citizens of Cook County, known as 4C, in 2020 to challenge the first proposed biomass production facility in Adel. The operation turns trees into wood pellets, which are then burned as an energy source. Residents were wary of the project and soon got busy petitioning, speaking at city meetings, and submitting comments during the permit process.

But in October of 2021, 4C received bludgeoning news: Not only had the Georgia Environmental Protection Division granted the permits they were challenging to a business calling itself Renewable Biomass Group; a second venture, Spectrum Energy USA, was applying for an air permit for their own pellet plant just a few miles away.

“We were flabbergasted,” Gear recalls. “A second wood pellet plant? Two in one city?”

Her reaction is in no small part because Gear knows the public health implications of biomass: Wood pellet processing generates dust that travels to nearby homes, carrying hazardous pollutants that can worsen respiratory and other health issues.

Spectrum plans to start operations on two neighboring polluted properties, including the site of a now defunct sawmill called Del-Cook. Once a big employer in town, Del-Cook looms large in the memory of Adel’s Black and Latino communities. Census data shows the population surrounding the site is 77 percent people of color and they live within one mile of the property, which is so riddled with contaminants, it was designated a toxic brownfield. Cancer has already taken a staggering toll on the neighborhood.

The Spectrum facility intended for this site will be more than twice the size of Renewable Biomass

Group’s nearby plant. In fact, with a proposed capacity of 1.2 million metric tons of forest-derived

biomass fuel per year, it would be one of the largest wood pellet plants in the world. According to climate experts, this isn’t just bad news for Adel.

Greenwashing biomass’s dirty reality

The biomass industry is growing fast because, even though it relies on clear-cutting forests, it calls itself renewable. According to Nicole Rycroft, executive director of the environmental nonprofit Canopy, it’s anything but. Our planet is grappling with two ecological crises: unprecedented biodiversity loss and climate change. Biomass, she says, is fueling both. A mature forest can absorb 40 times more carbon than saplings, and there’s a massive release of carbon when a forest is cut down, she explains. “It will take decades, if not hundreds of years, for that original loss of carbon to be back to neutral.”

Tell President Biden that biomass energy is not clean energy.

Yet, SELC Senior Attorney Heather Hillaker says, biomass producers are incentivized to push the “renewables” myth, because, in the European Union and the U.K., their customers — wood-pellet-fueled electric utilities — receive large subsidies intended for green energy, despite the fact that biomass fuel generates more carbon emissions than coal, according to data compiled by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Boosted by these subsidies, the industry has seen virtually unchecked growth, especially in the South.

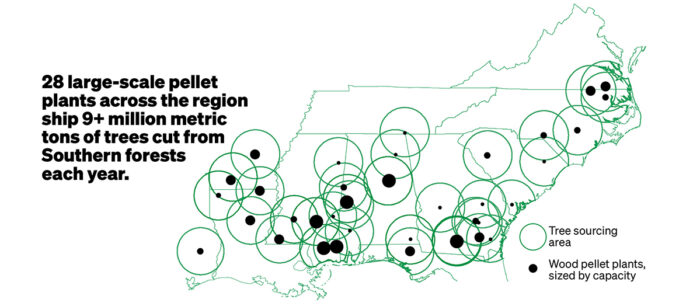

Currently, there are 28 large-scale pellet plants across the region, most of which opened only in the past decade. Today, they ship more than 9 million metric tons of trees and other types of biomass from Southern forests overseas annually. By SELC’s count, another 10 plants are in the works.

“In the South, we have mostly private land, and there are not a lot of regulations on what a landowner can do,” Hillaker explained. “There’s a big incentive for this industry to have access to this ‘wood basket’ in close proximity to ports.”

The clustering of these plants amplifies their impact, Hillaker says. And considering this North American coastal plain is a global biodiversity hotspot, ecologists are concerned about sweeping impacts. Looking at birds alone, there has been a dramatic decline in species found where biomass logging dominates.

The expansion of biomass in the U.S. is also a threat to public health. While its toxic byproducts are regulated, Environmental Integrity Project data shows that, in 2017, one in three wood pellet plants violated permitted limits. Even at legal limits, communities near these facilities have reported it necessary to wear masks outdoors.

State-level discrimination, federal action

As of 2018, every single wood pellet mill in North and South Carolina was in a low-income community of color. Across the South, these same neighborhoods were more than 50 percent more likely than affluent ones to become home to a wood pellet plant.

You can see a stark racial divide in the distribution of the industrial hazards, from a snapshot perspective and over time. That is not by accident. That is planned.

Dr. Sacoby Wilson, University of Maryland professor

Dr. Gear chalks the pattern of wood pellet plants opening specifically in Black and Latino neighborhoods up to systematic oppression.

“These issues are not new,” Gear says. They’ve gone on for so long, she says, that the presence of polluters in these communities becomes normalized — and citizens aren’t necessarily aware of their rights to things like clean air or safe water.

Dr. Sacoby Wilson, an environmental health scientist, environmental justice expert, and professor at the University of Maryland, says this is true in Adel, just as it’s true throughout the South.

“You have to look at Black Adel versus white Adel: The heavily industrialized area is primarily Black. The rest of the Adel is white,” Wilson says. “You can see a stark racial divide in the distribution of the industrial hazards, from a snapshot perspective and over time. That is not by accident. That is planned.”

In Adel, SELC is working with community members to break this pattern. Attorneys worked with 4C to negotiate a settlement with Spectrum around their air pollution permit. In an industry first, Spectrum agreed to purchase air monitors and provide pollution data to the community monthly, rather than annually. They also committed to cutting noise and traffic and providing air filters to local churches, daycare centers, and homes close to the facility. If they exceed pollution limits, they agreed to pay a hefty fine into a community fund.

“This facility is going to be in their backyard and, without this legal intervention, they may not have had a say,” says Senior Attorney Jennifer Whitfield, who led the negotiations.

SELC’s work on the settlement also made clear that Georgia officials are shirking their responsibility under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by “failing to take into account specific marginalized communities, and their past and present exposures to environmental burdens,” Whitfield says. SELC filed a complaint with the EPA about this overlooked obligation, which is still pending.

Adel resident Alicia Pinkney has four young grandchildren growing up not far from the biomass plant site in this city of 5,500. One day, they might apply for one of the jobs promised by the developers. But Pinkney, who is Black, is wary.

“We’re trying to live as long as we can, but those jobs they’re bringing in, it’s dangerous to our health,” Pinkney says, standing outside her trailer while the kids romp and play behind her. “I worry about their future here.”

Toward a future of cutting carbon

This is a pivotal moment for the biomass industry. According to Rycroft, Europe is beginning to realize that their biomass policy is “completely unsustainable.” Yet, Hillaker says, the U.S. may be at the brink of another explosion of industry growth. When President Joe Biden signed historic climate legislation into law last summer, the White House statement called the Inflation Reduction Act “the most significant action Congress has taken on clean energy and climate change in the nation’s history.”

“The priority really needs to be on true renewables, solar, wind, geothermal,” Rycroft says. “Equating tree plantations to a ‘renewable’ source — it’s not based on any of the credible science to date.”

SELC has been working for years to deepen the science around biomass’s impacts, from soil to smokestack, and to make that information accessible. In the coming year, the U.S. government will be making key decisions about how to dole out funding to support climate action.

“Biomass is not a genuine solution to climate change, and we shouldn’t make the same mistakes

that the E.U. made in categorizing it as ‘renewable’ and ‘carbon neutral,’” Hillaker says.

While it’s too late to stop the wood pellet industry from putting down roots in Adel, the settlement

with Spectrum provides the community with infrastructure for monitoring and accountability. And according to Gear, other communities can get ahead of biomass, if they stay vigilant: “We’re always

going to have to keep our eyes open for the next plant,” she says. “Our experience is a call to action

for other communities.”