Utility monopolies still reign in the South

Utility talk is notoriously wonky — even energy attorneys admit that.

David Neal has been advocating for affordable, clean energy solutions at the North Carolina Utilities Commission since 2015 and is currently advocating to reduce heat-trapping carbon pollution in the state Carbon Plan. He jokes that there are still certain issues that he can’t talk about “without people’s eyes glazing over.”

But utilities, like North and South Carolina’s regulated monopoly Duke Energy, have immense power over our everyday lives and our shared future, from the size of our energy bills to whether our collective power use eases or worsens climate change. And too often, our utilities seem at odds with energy affordability, reducing harmful pollution, and a meaningful, timely transition toward renewable energy sources like solar and wind.

To understand how traditional utilities work – and why they sometimes clash with customer and clean energy goals – it’s worth looking back to their establishment in the early 1900s. Our system for regulating utilities was devised, in part, to protect customers from unjust energy prices. Today, some experts believe that century-old structure has outlasted its original intentions.

Birth of regulated monopolies

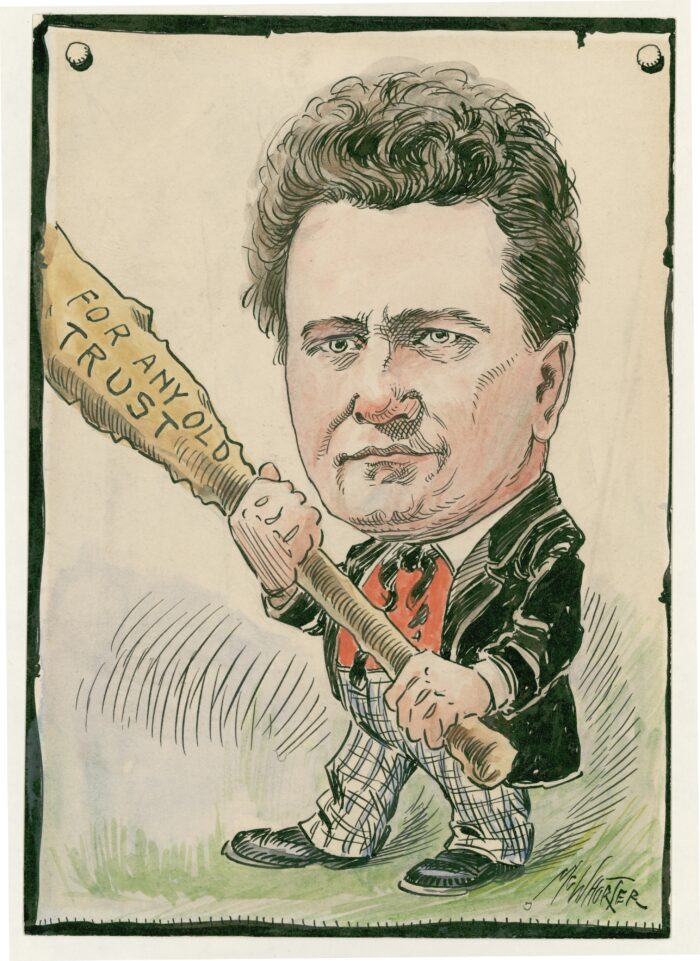

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States was changing fast. Telephones and motorcars were increasingly common, people were moving from the countryside into cities, and a brand-new industry called electricity was revolutionizing life.

Historian Richard Hirsh studies how US electric power companies developed. In the beginning, Hirsh says, they had little real oversight. Dozens of utilities might compete in a single city, resulting in wasted, duplicated wires and higher costs for customers.

Businessmen like Samuel Insull believed that, like railroads, utilities operated best as a “natural monopoly.” Unlike most other industries in which customers might benefit from competition, utilities, Insull argued, were most efficient when only one controlled a certain region.

But there was a potential problem with Insull’s model. “People were not too thrilled with the idea of monopolies,” says Hirsh.

Railroad companies had stoked fear about the danger of monopolies – they operated with little effective regulation, set exorbitant prices, and influenced politicians through bribery. If utilities were a “natural monopoly” too, it would be necessary to find a way to oversee them.

In Wisconsin, Progressive Era leaders like Governor Robert La Follette made it their mission to keep monopolies in check, creating the first state regulatory commission in 1907. The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin became a model for regulating utilities and provided a mechanism for setting the prices that utilities could charge.

“Cost-of-service regulation meant that utility monopolies couldn’t set their own prices on power,” Neal explains. “Instead, their profits were based on the costs of the infrastructure they built—power plants, poles, wires — plus a return. The more they built, and the more expensive the infrastructure they built, the more money they could earn.”

A key role for regulatory commissions was to make sure that utilities did not “gold plate” those investments – that is, overbuild just to earn a larger return for their shareholders.

The new regulatory structure aimed to protect the public and offer stability to industry leaders like Insull, who could now ensure that they would recover the costs of growing the grid. Hirsh adds that throughout much of the 20th century, as demands for power steadily increased, cost-of-service regulation worked: utilities built more powerplants at larger scales, and the price of electricity declined for customers.

The high price of cost-of-service today

Around a decade ago, reporter and Volts creator David Roberts began to wonder why utilities were slow to adopt clean energy solutions like energy efficiency, net metering, and rooftop solar.

“It seemed like a good thing for homeowners, for the grid, for society,” he remembers thinking. “Why would utilities be against it?”

The answer, he says, “has illuminated everything ever since.” That answer would be a certain 100-year-old regulatory structure.

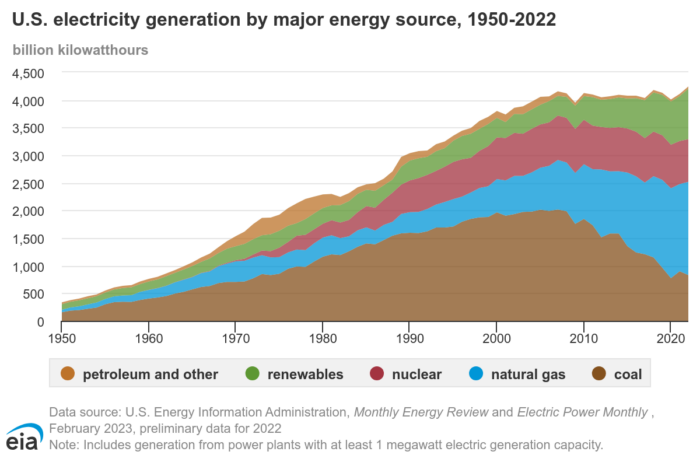

For the last twenty years, energy demand hasn’t grown as rapidly as it did in the 20th century – and many clean energy solutions don’t necessarily require costly, enormous, utility-owned infrastructure.

“If you can reduce energy consumption with efficiency, then you don’t need to build as much,” says Roberts. “Or if you can generate power from your roof, you don’t need to build as much. Those things are very good for consumers. They’re good for everyone, except the utility.”

In North and South Carolina, where most people get their power directly from Duke Energy, SELC’s Neal says, “Cost-of-service regulation biases the utility toward bigger, more expensive projects.” That includes proposals in recent North Carolina rate cases to spend billions on excessive grid upgrades – with customers bearing the cost.

It also includes Duke’s proposed North Carolina Carbon Plan, says Neal, that would delay the state established deadline for reducing carbon pollution, allow construction of new polluting fossil fuel plants, and focus investments on expensive, unproven technologies like small modular nuclear reactors.

In much of the southeast, monopolies still reign. Bills like North Carolina’s 2007 REPS law have opened the door for increased reliance on clean energy but have not fundamentally changed the utility business model. Yet Neal says, “Reform is possible.”

Reform is possible.

David Neal, Senior Attorney

Most other regions of the United States have moved away from the model established in the early 20th century toward competitive energy markets that allow more independent energy producers to sell power to utilities. Because renewables are among the cheapest forms of energy, these markets could allow power costs to lower and clean energy to take off, with one recent report suggesting that a southeastern energy market could create $384 billion in regional savings, and another report suggesting that South Carolina alone could save up to $362 million annually.

Our shared future

Utility regulation might be acronym-filled and jargon-heavy, but Neal says utilities’ wonkiness too often protects them from scrutiny. “It makes it easy for utilities to do what they want without much public oversight,” he says. “And it’s crucial that Carolinians pay attention to achieve a cleaner, safer, more affordable future.”

Our regulatory structure was designed, in part, to protect customers from the excessive political and financial power monopolies could wield. As people today raise their voices in support of shifting away from fossil fuels toward clean and cost-effective energy sources like solar, efficiency, and wind, are regulated monopolies still serving their original purpose?