Clean Water Act proposal drastically cuts protections against pollution

SELC continues to battle a Trump administration proposal that would radically reduce the nation’s number of streams and wetlands protected by the Clean Water Act. This proposal is a gift to polluting industries that would cause serious problems for those who depend on clean water and streams for drinking, farming, recreation, and economic development.

“This would be the biggest rollback in the history of the Clean Water Act,” said Blan Holman, leader of SELC’s Clean Water Defense Initiative. “They’re looking to gut protections that have been in place since Richard Nixon was in office.”

The Clean Water Act works by prohibiting unpermitted pollution in our waterways. To get a permit, companies must adhere to pollution limits and use the best-available pollution control technology. It is an important tool that state and local officials use to maintain the safety of our water sources, and it recognizes that pollution flows downstream—to protect our nation’s water quality overall, we must protect the upstream tributaries that flow into downstream rivers.

The new rule proposed by the Trump administration’s Environmental Protection Agency takes an axe to upstream protections. It would remove Clean Water Act protection from all ephemeral tributaries—those that flow in direct response to rain events. The proposal also asks for input on stripping protections of intermittent streams — those that flow part of the year, not typically every day of every year – and even small perennial streams that have flow throughout the year. All of these streams flow into our larger bodies of water and carry pollution downstream.

Making a bad idea even worse, the proposal includes definitions that are hopelessly complex. The definition of an intermittent stream, for example, requires a statistical analysis of 30 years of data. These types of definitions will require hiring consultants and lawyers.

“They proposed this rule in the name of clarity and to clean up uncertainty,” said Holman, “but the reality is anything but clear. It’s a mess to interpret and it’s a disaster for water quality.”

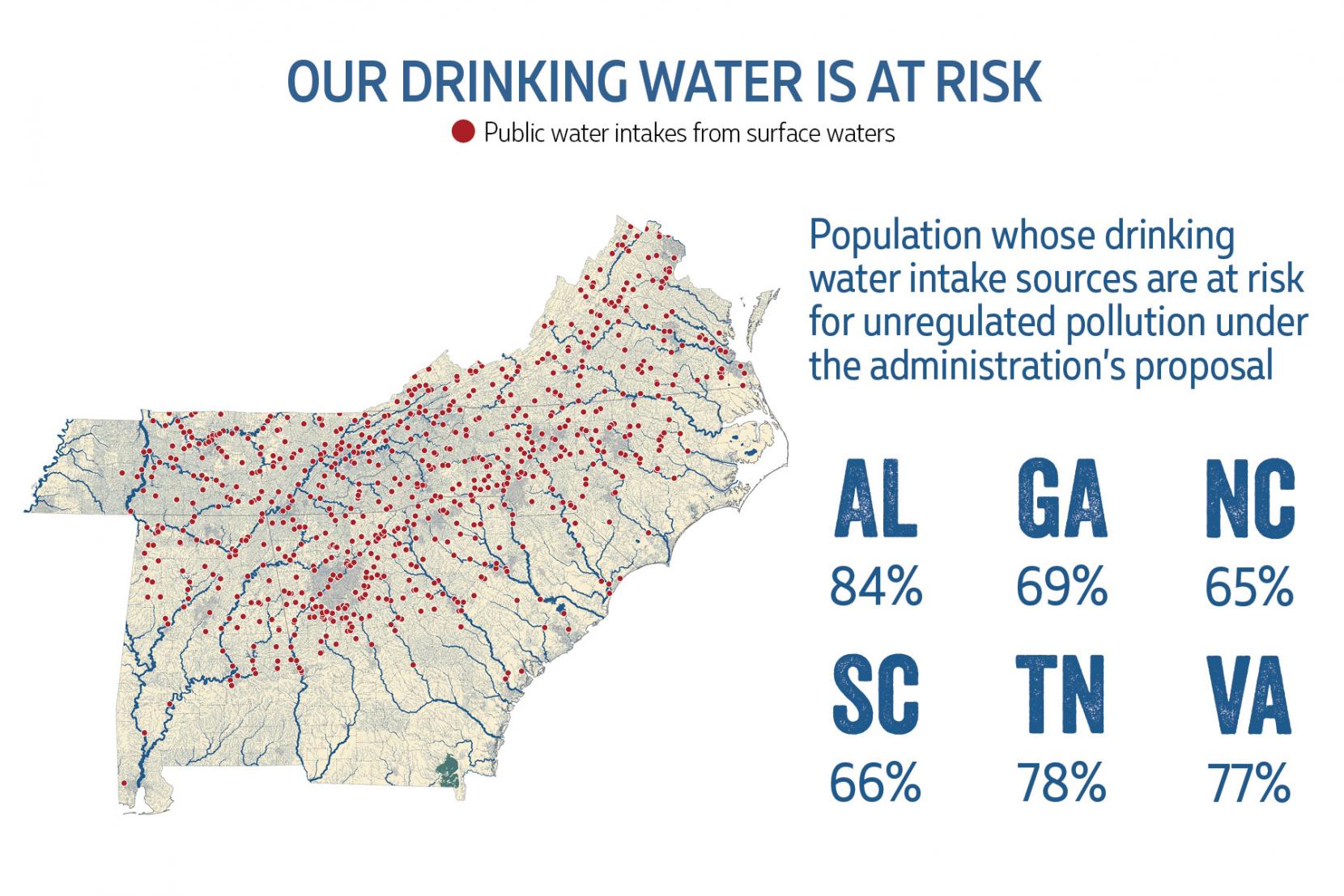

Even EPA’s conservative estimates suggest that more than half of the streams in the country could lose protection. In SELC’s six states, more than 290,000 miles of streams would be threatened.

The proposal is even worse for wetlands, which play a critical role by storing floodwaters and trapping pollution so it doesn’t flow downstream. “We are talking about losing protections for more than half of the nation’s wetlands,” Holman said. “The blows to water quality, flood protection, and wildlife habitat are mind blowing.”

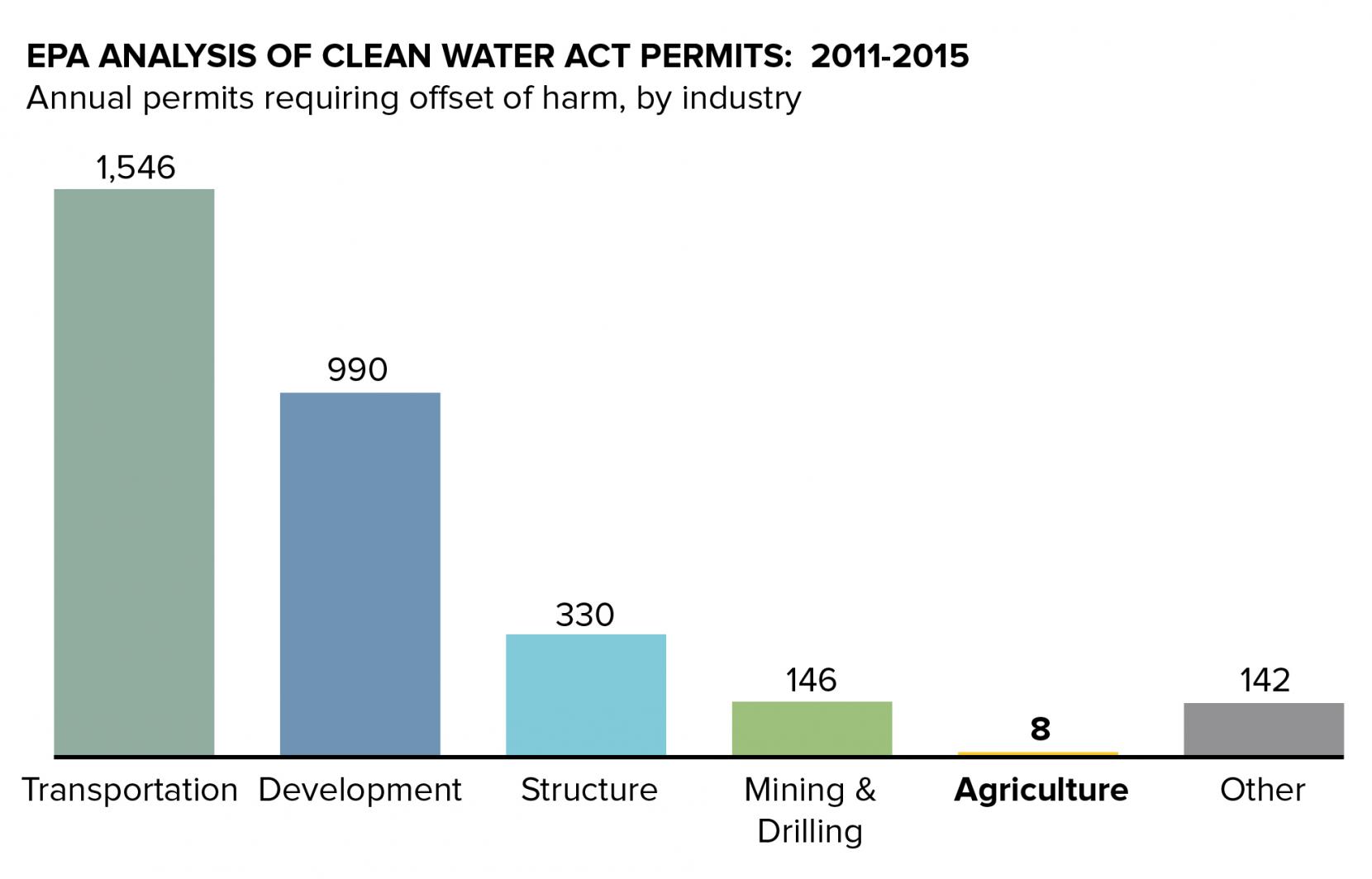

While the administration has peddled its proposal as benefiting farmers, the real forces behind it are industries that would pave, fill, and destroy streams and wetlands on a massive scale. EPA’s own analysis shows that agricultural interests seek a tiny fraction of permits, while heavily polluting industries seek a far greater number.

Gutting clean water protections may save polluting industries money, but the cost would be passed onto the public downstream. “At the most basic level, everybody who drinks water should be concerned,” said Holman. “Every day we learn more about contaminants in our water — microplastics, Teflon chemicals, other toxins. The Clean Water Act is the main shield against that. We should be making the shield stronger and bigger, but they want to make it weaker and smaller.”

Ending protections for smaller streams spells trouble for the larger streams, rivers, lakes and reservoirs they flow into. “When you shrink the shield, you’re not just losing protection for the waters directly affected, but you’re eroding protection for everything downstream,” Holman said. “Science shows you can’t protect navigable waters without protecting their tributaries, which is why tributaries have always been protected by the Clean Water Act.”

Safe drinking water is not the only thing at risk. Those who enjoy fishing, swimming, paddling, and other recreational uses could encounter a lot more pollution in those waters if this rule takes effect.

Holman noted that the rivers at the heart of recently revived city centers across the Southeast — like the Reedy River in Greenville, S.C., the James River in Richmond, and the Tennessee River in Chattanooga — are in much better condition now because of the Clean Water Act. “A lot of folks don’t remember that many of the rivers that are now centerpieces and living parts of revived city centers were cesspools,” Holman said. “Now they are civic gathering places and the heart of their communities, thanks to the Clean Water Act.”

At the most basic level, everyone who drinks water should be concerned.

Blan Holman, Senior Attorney

SELC’s defense of the Clean Water Act began with the Trump administration’s first bid to weaken it: EPA’s suspension of President Barack Obama’s Waters of the United States rule, established in 2015. That measure actually did work to clarify uncertainty about the act’s jurisdiction, while slightly expanding its reach.

After the administration finalized its suspension of the 2015 rule, SELC went to federal court on behalf of a coalition of conservation groups. In the summer of 2018, the court struck down the suspension rule as unlawful because the administration had failed to tell the public what it was doing or allow meaningful public input.

Meanwhile the administration was moving full steam ahead on its affirmative plan to gut the Clean Water Act. On February 14 of this year, it formally announced its proposal to severely curtail protections for streams and wetlands — going far beyond a repeal of existing standards to strip away defenses that the nation has relied on for decades. The proposal opened up a 60-day public comment period, which closes on April 15. SELC is working closely with partners across the Southeast to raise awareness of all that’s at stake and opposing the rule.

Holman said public comments are vital for several reasons. First, because the administration must, by law, consider them before finalizing the rule, a large volume of comments ensures that the agencies cannot move hastily when dismantling long-held protections. Second, strong public opposition can deter the agencies from pursuing even more aggressive cuts. Finally, comments can counter misleading claims that the public supports an anti-environmental agenda.

Ultimately, if the administration finalizes its Clean Water Act assault despite public opposition, SELC will be prepared to fight back. “While we certainly hope the agencies come to their senses and comply with the law, we are not betting on it. There is too much at stake to sit by and watch. If the administration insists on jeopardizing the water our families and communities depend on, we will be back in court,” Holman said.