SELC's Magazine

Highlights from this issue

Fighting forever chemicals

New protections for old forests

Transforming coal mines to shared solar

Want to receive SELC’s Magazine? Sign up below.

Fighting forever chemicals

PFAS ARE PERSISTENT BUT SO ARE THOSE HOLDING POLLUTERS ACCOUNTABLE

By Stephanie Hunt, photos by Cornell Watson

Carrol Olinger never planned on being a rabble-rouser.

She and her family loved the quiet, rural life in Hope Mills, North Carolina — a small town an hour south of Fayetteville, named for the cotton mills nearby. For years, Olinger was a teaching assistant at Alderman Road Elementary School and led Girl Scout adventures, taking her troop fishing along the Cape Fear River.

“I enjoyed scuba diving and snorkeling in it too. It’s still fun even if you can’t see anything,” she says of the 202-mile waterway — the state’s largest river system, which like many tannin-stained rivers, is often murky, like diluted chocolate milk. “But I don’t anymore.” Not since Olinger, her neighbors, and the 500,000 North Carolinians downstream whose drinking water comes from the river learned that natural tannins aren’t the only thing muddying the Cape Fear.

These days, Olinger has traded scuba for diving deep into the river basin’s long history of industrial pollution, including the 40-plus years that DuPont and, more recently its spin-off, Chemours, have been discharging toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly known as PFAS, into the Cape Fear and contaminating groundwater. Like a seasoned scout leader, she’s determined, feisty, and outspoken about how that contamination disproportionately impacts “people who look like me — Brown and Black people. Those who don’t have health insurance and can barely pronounce polyfluora-whatever or reverse osmosis, much less afford it,” Olinger says.

“I’m an accidental activist,” she laughs, though she knows that these so-called “forever chemicals” are deadly serious. Their common name speaks to the durable, resilient qualities that make them useful in innumerable products — waterproof, stain-resistant, nonstick products, electronics, medical devices, beauty products, explosives, dental floss, you name it — but also to the fact that they don’t break down in the environment and our bodies. PFAS have been linked to cancer, kidney and liver disease, immune dysfunction, endocrine disruption, infertility, asthma, and low birth weight, among other conditions. “Here I am on dialysis, with no family history of kidney disease,” Olinger says.

When the Wilmington StarNews broke the story in June 2017 that the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority was contaminated by GenX, a PFAS compound discharged by Chemours, “It started making sense, why I was sick and the fish in my fish tank were dying,” says Olinger.

She is now an area organizer for Action NC, a statewide advocacy group addressing social and economic inequality. Realizing there was more to the story, “Dig deeper!” became Olinger’s rallying cry at local protests and public hearings.

SEEING THE SOUTH

New protections for old forests

Photos by Jerry Greer

Some of the oldest trees on the East Coast tower over a corner of far west North Carolina. The Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest is tucked so far into the Blue Ridge Mountains that swaths of it were never commercially logged, meaning some of its oldest, most majestic trees are 300 to 400 years old. These towering forests have provided respite for generations and inspired countless people to connect with something greater than themselves. The forest also stores centuries of carbon, blunting the impacts of climate change, and pulling more from the atmosphere each year.

While the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest is protected, other mature and old-growth forests on public lands, including many in the South, are routinely logged, releasing stored carbon to the atmosphere. Instead of cutting down these incredible forests, we should recognize their importance in the fight against climate change. Click below to sign our petition calling for protections of old-growth forests.

Urge the Biden administration to protect old-growth forests.

Transforming coal mines to shared solar

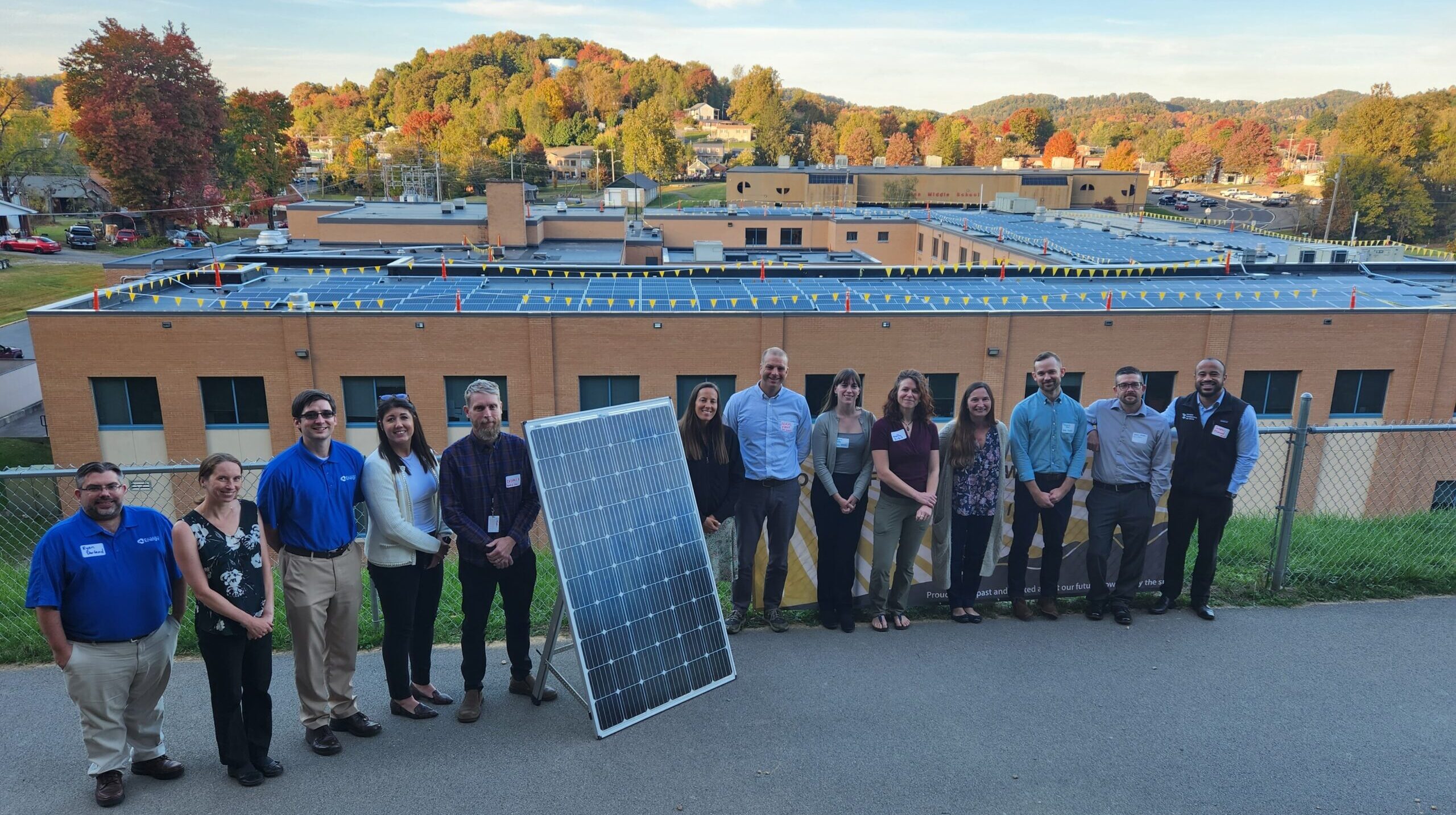

Generations of coal miners have celebrated their child’s first day of school at Wise Primary School in southwest Virginia. Not long ago, the school became a symbol for the region’s transition to clean energy, opting for the lower costs and cleaner air that come with solar power.

Coal fields to solar panels

Watch to hear Staff Attorney Josephus Allmond share one community’s experience of moving from coal to solar and the many benefits generated.

Getting to that point took many years and intentional conversations in groups like the Solar Workgroup of Southwest Virginia, where SELC is a member. Just one year after solar panel installation, the school saved nearly $8 million in energy costs that will be reinvested into the school system. It is one of several schools in the area now tapped into the benefits of solar, an option that wasn’t even available before the Solar Workgroup’s efforts got underway.

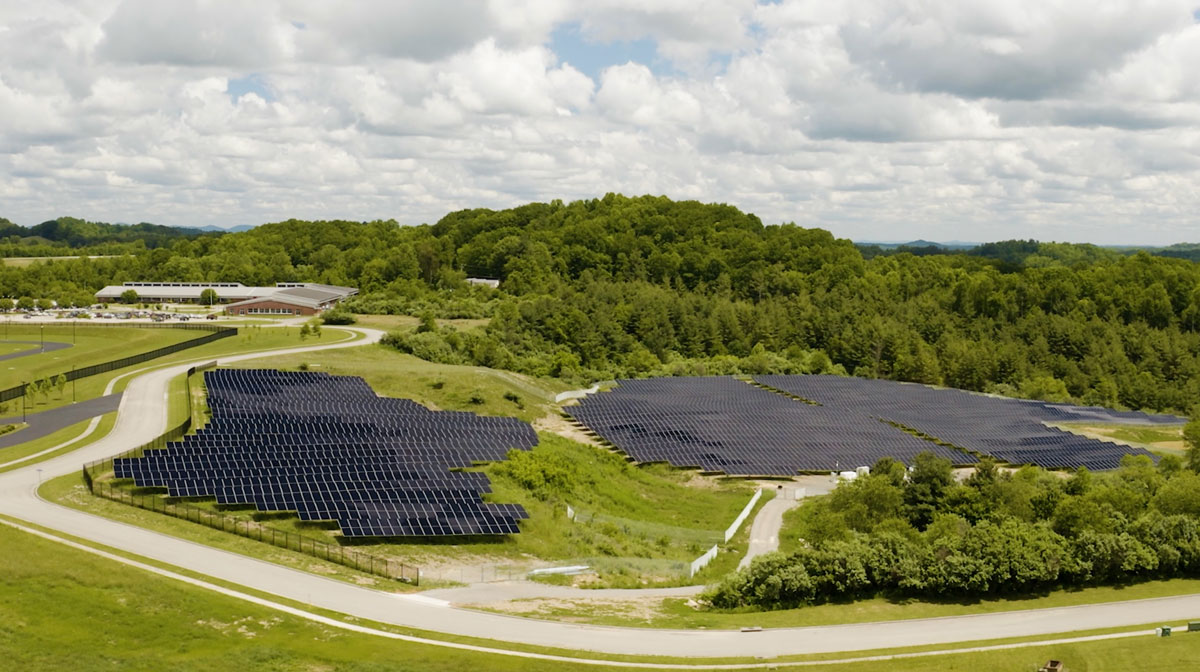

Now, with that experience under folks’ belts, and new funding thanks to the 2022 passage of landmark federal climate legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, historic coal-producing states like Virginia have an unprecedented opportunity to reenergize their economy and implement environmentally sustainable solutions that work for us all.

The approach provides an equitable practice that efficiently and cost-effectively shares clean energy benefits with entire communities without placing a financial burden on individuals.