Georgia women are fighting to protect their neighborhoods

On the outskirts of Atlanta, another case of Southern community activists pushing back against a major polluting facility is currently playing out in court, and Black women are leading the charge.

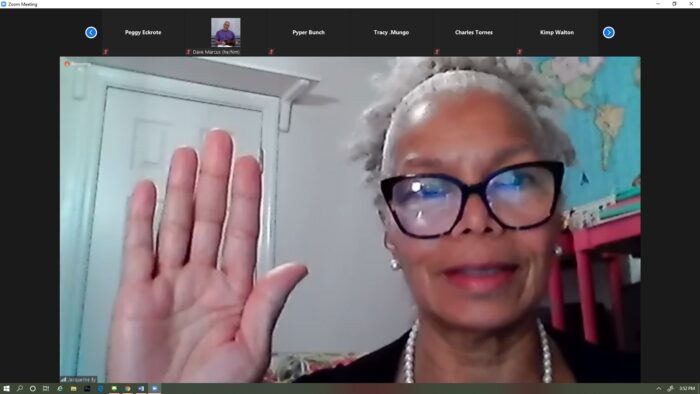

“As a Black woman, we have fought on so many levels to be heard, to be accepted,” says Windsor Downs resident Jennifer Wilson, who lives directly across the street from the site where a solid waste handling facility is proposed. “It’s almost like [fighting back] is par for the course — it’s just something that we, especially my generation, have learned to do.”

Wilson is a member of Citizens for a Healthy and Safe Environment, an organization focused on protecting communities in south DeKalb County from environmental injustices.

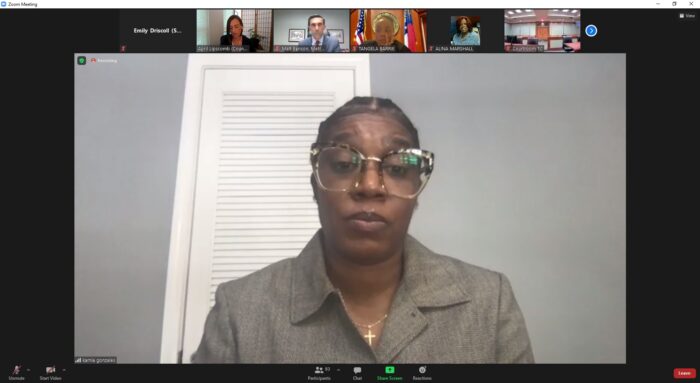

“My brother teases, but he says, ‘Y’all hardly have any money, but you’re always in these battles that you don’t lose,’” says Renee Cail, President of CHASE. “And I said, ‘I’m not bragging about that because in life, we win some, we lose some. But we’ve just been blessed not to have lost any and only God knows why.”

A bad neighbor

For nearly two years, CHASE’s efforts have focused on protecting surrounding neighborhoods from Metro Green Recycling, a proposed solid waste handling facility that would bring hundreds of tons of waste to the site per day — and along with it, plenty of disturbing noise and odors, dust and fine particulate matter, and heavy metals and chemicals that could contaminate an on-site tributary of the South River.

When Cail saw the clear cutting and other activity on the facility’s site, she started to research what was happening and knew it was time to sound the whistle.

Somewhere between spotting each other on virtual city council meetings related to the project and getting connected by Georgia House of Representatives member Doreen Carter, Cail and Wilson say their grassroots campaign was born.

Five women took it upon themselves to create Stop Metro Green, a campaign of CHASE.

“And then one Saturday morning all of us got together, passing out flyers on foot,” says Cail.

Proof that there’s power in numbers, they have drafted approximately 50-100 participants who are now informed on Metro Green’s proposal and active in opposing it.

“We knew that the more people we had involved, the easier it would be for us to engage more people and collaborate with other organizations,” says Cail. “Once people understand that they have a vested interest, some power, and feel confident to talk and share their voice, it’s easier.”

Along with air and water quality concerns, neighbors are worried about noise pollution, heavy truck traffic, and vibrations that could damage their homes. Although it’s unclear exactly what activity was happening on site at Metro Green, at least one neighbor has reported a crack in the foundation of her house from the turbulence. Others have reported cracked driveways, dust, and odors, in addition to emotional and psychological stress as a result.

Perhaps more notably, when concerns about the project started coming to light, many houses went up for sale. Despite so many neighbors moving, Wilson says she refuses to join them.

“It’s just the principle,” she says. “If I decide to sell, it’s because it’s something we’ve decided as a family to do. Not because a company has decided they’re going to put their business here and run me away.”

Over a dozen homes in Miller Woods are within 100 feet of Metro Green’s boundary, and Miller Grove Middle School is less than a mile down the road. Thousands of residents live directly across the street from the facility in unincorporated DeKalb County, including Crestview Apartments, Windsor Downs subdivision, and other neighborhoods where some have lived since the 1980s.

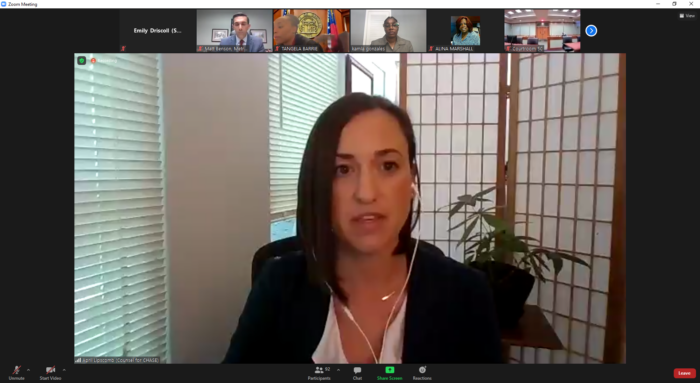

If allowed to proceed, the facility would accept an average of 400 tons per day of concrete, metal, wood, rock, drywall, asphalt shingles, and other construction and demolition solid waste, explains Senior Attorney April Lipscomb. Metro Green would also crush large quantities of concrete at the northern end of the site, which borders the backyards of neighbors in the Stonecrest subdivision Miller Woods.

SELC is representing CHASE in its case against Metro Green, most recently winning an injunction in September to temporarily stop construction and operation of the facility.

This was just a reminder that when you know an injustice has happened, that you need to fight the good fight all the way to the end.

Jennifer Wilson, CHASE member

Wilson says her heart beat fast as the DeKalb County Superior Court judge read the favorable verdict, and she almost cried tears of joy.

“This was just a reminder that when you know an injustice has happened, that you need to fight the good fight all the way to the end,” she adds.

CHASE and SELC are also charging that the City of Stonecrest lacked authority to approve the project at the local level and that Metro Green concealed from and misrepresented to the Georgia Environmental Protection Division key information when it applied for its state solid waste handling permit.

CHASE raised these legal concerns to EPD Director Rick Dunn in September 2019 and asked him to revoke the facility’s permit. Director Dunn ignored CHASE’s request, however, and declined to make a decision. Our suit aims to show that Director Dunn should revoke Metro Green’s permit and must issue a decision on CHASE’s request immediately. Our suit also aims to show that EPD has the authority to revoke the facility’s permit.

“Far from following through on its assurances to ‘be a good neighbor,’ Metro Green decided to forge ahead without considering the harm of its actions on its neighbors,” says Lipscomb, the lead attorney on the case. “Halting the project now is a necessary step to prevent Metro Green from inflicting additional harm on south DeKalb and Stonecrest communities.”

Cail maintains that neighbors are not willing to compromise the quality of their air, water, and livelihoods for a polluting private business.

“South DeKalb neighborhoods should not have to bear the brunt of the environmental injustices and health risks that come with these types of industrial facilities, and we will not stand for having our backyards used as a dumping ground,” she says.

A long road

Their battle against Metro Green has been met with multiple obstacles, including a pandemic that highlighted the importance of clean air and the right to feel safe in their own homes and yards, and limited neighbors’ ability to safely organize in-person, plus a lawsuit aiming to silence them.

In January 2021, members of CHASE were served with meritless claims that amount to a SLAPP suit, or a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, for protesting and voicing their opposition to Metro Green’s proposed facility. There is a long history of private entities employing these suits to silence opposition.

SELC filed an anti-SLAPP motion in order to protect CHASE’s First Amendment rights and to strike Metro Green’s claims seeking monetary damages for slander, libel, and tortious interference with contractual and business relations.

A DeKalb County Superior Court has ruled in favor of CHASE by striking Metro Green’s meritless claims against the group.

“We have the right to protest,” assures Cail. “It’s kind of unsettling when you’re sued for something but I just feel like we have to continue to stand for what we know is right.”

Her neighbor Wilson agrees. As a Black woman, she says it’s not the first time someone has tried to silence her.

“You gotta be willing to take those kinds of hits,” she says. “It’s almost like what [former Congressional Georgia Representative] John Lewis said all the time: ‘You need to get in good trouble.’ This really is good trouble.”

Adds Wilson, “There is no failure in making the attempt to stand for righteousness and that’s what we did. And so far, we’ve prevailed.”

SELC is behind CHASE as it continues its mission to stop Metro Green. And the group plans to keep spreading its message that everyone deserves a safe environment.

“I feel very strongly that everybody—I don’t care if you’re white with purple dots—everybody has the right to clean air, clean water, clean soil, and also to a good quality of life,” says Cail. “We need to band together because there’s enough on this planet for everybody to live well.”