Dividing highways: How historic Black communities are seeking justice

Southern towns come in all shapes and sizes, with many sharing the same history of racial segregation and an unending cycle of environmental injustice. Big or small, these injustices persist and many of them are centered on the movement, or desire to stop movement, of Black people.

To fully understand how and why these injustices persist, one can first go back to how most Black communities in the South came to exist.

It’s impossible to talk about Southern places and spaces without talking about where descendants of enslaved people live, how we got there, and the intricate bond we have with Southern landscapes.

Chandra Taylor-Sawyer, Environmental Justice Initiative Leader

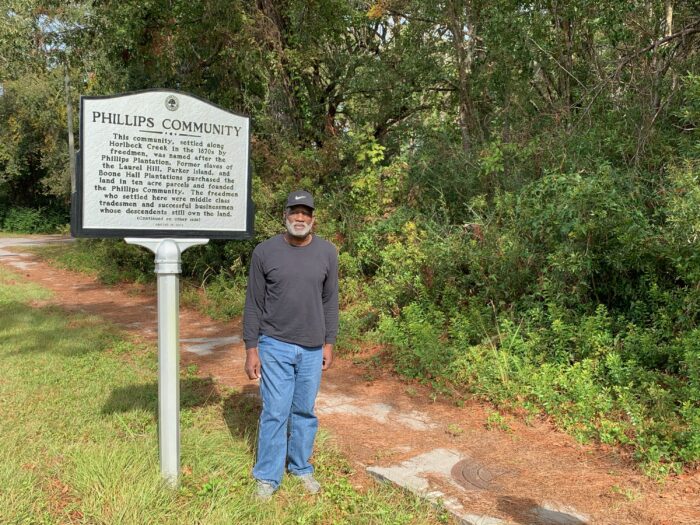

The Phillips Community in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, is one example. This community was settled on and named for the former Phillips Plantation by freed people in the 1870s. In recent years developers have eyed the area more than once and, most recently, the community has been threatened by the proposed expansion of Highway 41, which has already disrupted and displaced the community.

Completed in 1942, Highway 41 cuts through the center of the Phillips Community. The road split family properties in half, creating two dangerous lanes for pedestrians to cross. As with most urban renewal efforts and building out of this country’s interstate highway system, members of the community were not included in planning efforts or asked for their opinions on the highway, yet have been left to deal with the sound and air pollution that comes along with such highways.

“You see this across the nation. Black communities have been broke up time and time again and now there is the desire to increase capacity on these roads, which more often than not, will create more pollution and safety hazards directly impacting these communities,” said Chris DeScherer, director of SELC’s Charleston office.

While the argument has been made that these issues aren’t the fights for environmentalists to take on, the relationship of movement, Black individuals and communities, and spaces throughout the South are forever intertwined and at the heart of every racial justice movement throughout the South, whether it’s been in housing, land ownership, environmental, or now climate change.

Chandra Taylor-Sawyer, leader of SELC’s Environmental Justice Initiative, wants people to keep this top of mind.

“It’s impossible to talk about Southern places and spaces without talking about where descendants of enslaved people live, how we got here, and the intricate bond we have with Southern landscapes, whether that be roadways or waterways. Highways, which ultimately can keep people in one place just as much as they can move others out of it, play an important part of that history,” Taylor-Sawyer said.